Travel often makes people more alert to danger. You check neighborhoods, avoid risky situations, and take recommended vaccines before stepping on a plane. Most travelers believe they’ve covered all the obvious threats. What often goes unnoticed is something far more ordinary and far more intimate: food. What ends up on your plate can sometimes pose risks that are just as serious as environmental hazards or infectious diseases

Around the world, certain foods sit right on the edge between delicacy and danger. Some cause nothing more than mild food poisoning when mishandled, while others can lead to organ failure or death if prepared incorrectly. In many cases, the danger isn’t obvious. The food may look fresh, smell fine, and be deeply rooted in local tradition. Yet behind the cultural appeal, chemistry, bacteria, or natural toxins quietly create real risks.

The foods below are not meant to inspire fear, but awareness. Many of them can be eaten safely under the right conditions. Others demand expert preparation or should be avoided entirely unless you truly know what you’re dealing with.

Absinthe

Absinthe is a high-proof alcoholic drink made from wormwood leaves blended with herbs such as green anise and fennel. First developed in Switzerland during the late eighteenth century, it quickly gained popularity in France, where it became associated with artists and writers. Famous names like Picasso, Van Gogh, and Hemingway were known to drink it, in part because it was cheaper than wine and far stronger.

For decades, absinthe carried a reputation for inducing hallucinations and madness. These claims eventually led to bans across Europe and the United States that lasted nearly a century. The U.S. only lifted its prohibition in 2007, after regulations were introduced to control its chemical content.

The controversy centers on thujone, a compound found in wormwood. High doses of thujone have been linked to seizures, kidney failure, muscle breakdown, tremors, dizziness, and disturbing dreams. Animal studies showed increased death rates when mice were exposed to large amounts, leading some to label absinthe as a poison.

Modern absinthe, when properly produced, contains thujone levels far below dangerous thresholds. The real risk comes from poorly made or illegally sourced products, which may contain unsafe concentrations. As with most high-alcohol spirits, moderation and source quality make all the difference.

Ackee

Ackee is a striking fruit with bright red skin and glossy black seeds, widely used in Jamaican cuisine. Despite its beauty and popularity, it carries a serious risk when eaten improperly. Only fully ripe ackee that has naturally opened can be considered safe after cooking.

Unripe ackee contains toxins concentrated in its seeds and flesh that can cause severe poisoning. Symptoms may include vomiting, weakness, and dangerously low blood sugar levels. Although poisoning cases are relatively rare in regions where ackee is traditionally consumed, improper preparation can be fatal.

Because of these risks, the United States restricts ackee sales to canned products that meet strict safety standards. Outside Jamaica, ackee should only be eaten when prepared by experienced professionals. Harvesting or preparing it without proper knowledge is strongly discouraged.

Namibian bullfrog

Frog legs are commonly eaten in parts of Europe, but in certain African regions, the entire frog is consumed. The Namibian bullfrog is especially sought after due to its large size and high fat content, making it appear like a valuable source of protein.

The danger lies in the frog’s natural defenses. Namibian bullfrogs produce toxins intended to deter predators. These toxins are especially concentrated in younger frogs that have not yet mated. When consumed, they have been linked to kidney failure and, in severe cases, death.

Unlike many other dangerous foods, this is not a matter of improper preparation. Even cooked bullfrog meat can retain harmful compounds. For this reason, eating the Namibian bullfrog carries inherent risk, regardless of culinary skill.

Bean sprouts

Bean sprouts appear harmless and are often associated with healthy eating. The problem lies not in the sprout itself, but in how it is grown. Sprouts thrive in warm, moist environments, which also happen to be ideal conditions for bacterial growth.

As a result, bean sprouts have been linked to outbreaks of E. coli, salmonella, and listeria. These bacteria can cause severe illness, particularly in children, the elderly, and those with weakened immune systems. Over a twenty-year period, thousands of illnesses and multiple deaths were traced back to contaminated sprouts.

The risk can be significantly reduced through cooking. Heat effectively kills the bacteria commonly found on sprouts, making them much safer to eat. Raw consumption, however, continues to carry a level of risk that many people underestimate.

Blood clams

Blood clams, also known as cockles, are considered a delicacy in parts of China and Southeast Asia. They are typically boiled and served as street food or in markets. Their danger comes from the environments in which they are harvested.

Blood clams often live in polluted coastal waters, where they can accumulate viruses and bacteria harmful to humans. These include pathogens responsible for hepatitis A, typhoid fever, and dysentery. Unlike some contaminants, these organisms may survive light cooking.

In 1988, Shanghai banned blood clams after an outbreak of hepatitis A affected more than 300,000 people and caused multiple deaths. Despite this history, blood clams still appear in markets, reminding consumers that tradition does not always equal safety.

Cassava

Cassava is a starchy root vegetable that feeds hundreds of millions of people across Africa, South America, and parts of Asia. When properly prepared, it is a safe and reliable food source. The danger appears when cassava is eaten raw or processed incorrectly.

Raw cassava contains linamarin, a naturally occurring compound that breaks down into hydrogen cyanide inside the body. Even small amounts of improperly prepared cassava can expose a person to toxic levels of cyanide. Symptoms may include headache, dizziness, confusion, agitation, and difficulty breathing. In extreme cases, poisoning can be fatal.

Traditional preparation methods such as soaking, fermenting, drying, and thorough cooking are essential for removing these toxins. These practices are not optional but critical to safety. Cassava’s risk lies not in the plant itself, but in ignoring the knowledge developed over generations to make it edible.

Casu marzu

Casu marzu is a traditional cheese from Sardinia that is intentionally left to decay. The cheese is exposed so flies can lay eggs inside it. When the eggs hatch, the larvae digest the cheese, transforming it into a soft, fermented product.

The danger comes from consuming the cheese while live larvae are still present. These larvae can survive stomach acid and potentially damage intestinal tissue. Eating casu marzu has been linked to severe gastrointestinal illness, abdominal pain, and infection.

Due to these risks, casu marzu is illegal in many countries. While some locals continue to eat it as a cultural tradition, it remains one of the most extreme examples of food crossing into biological hazard territory.

Dragon’s Breath pepper

Dragon’s Breath is among the hottest peppers ever cultivated. It far exceeds the heat of common chili peppers and even surpasses previously record-holding varieties. Its intensity comes from extreme concentrations of capsaicin, the compound responsible for heat sensation.

Capsaicin at very high doses does more than burn the mouth. It can trigger intense pain, inflammation, airway constriction, and in rare cases anaphylactic shock. Some individuals have experienced breathing difficulties after consuming extremely hot peppers.

While often eaten as a challenge rather than food, Dragon’s Breath demonstrates how naturally occurring compounds can overwhelm the body’s defenses. For most people, this pepper is better admired than consumed.

Echizen kurage (Nomura’s jellyfish)

Nomura’s jellyfish is the largest jellyfish species in the world, often growing larger than an adult human. While it is sometimes served as a delicacy in parts of East Asia, it carries serious risks when not prepared by experts.

The jellyfish contains toxic compounds that can cause gastrointestinal distress, headaches, muscle cramps, and neurological symptoms. In severe cases, poisoning has led to coma or death. The toxins are not evenly distributed, making incomplete preparation especially dangerous.

Specially trained chefs use precise techniques to remove or neutralize these toxins. Any deviation from proper preparation can leave enough residue to cause illness, making this food one of the most technically risky seafoods to consume.

Elderberries

Elderberries are commonly used in syrups, supplements, and traditional remedies. While ripe, cooked elderberries are generally safe, raw or unripe berries contain toxic compounds that can cause serious digestive upset.

Symptoms of poisoning include nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea. The leaves, stems, and seeds are particularly dangerous and should never be consumed. Cooking destroys the harmful substances, which is why proper preparation is essential.

Mistaking elderberries for other edible berries or consuming them raw is a common source of poisoning. Their risk lies in the narrow line between safe and unsafe preparation.

Feseekh

Feseekh is a fermented fish traditionally eaten during spring festivals in Egypt. The fish is salted and dried for extended periods, creating conditions that can allow dangerous bacteria to grow if not carefully controlled.

Improper fermentation can lead to the presence of Clostridium botulinum, the bacterium responsible for botulism. This toxin attacks the nervous system, causing paralysis that can spread from facial muscles to the lungs.

Each year, hospitals treat cases of feseekh-related poisoning. The dish’s danger lies in the fine balance between fermentation and contamination, where a small mistake can have life-threatening consequences.

Greenland shark

The Greenland shark is one of the most unusual creatures humans consume. It can live for several centuries and survives in icy, deep waters where few predators exist. While fascinating biologically, it is not naturally safe to eat.

Fresh Greenland shark meat contains high levels of urea and trimethylamine oxide, compounds that are toxic to humans. Consuming the meat without proper preparation can cause symptoms similar to extreme intoxication, including dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and loss of coordination.

In Iceland, the meat is traditionally fermented and dried to neutralize these toxins, producing a dish known as hákarl. When prepared correctly by experienced producers, it can be eaten without serious harm. Outside of these controlled traditions, however, Greenland shark remains a hazardous food best avoided.

Larb (raw meat salad)

Larb is a traditional dish in Laos and neighboring regions, often prepared as a salad made with raw or lightly cooked meat. The type of meat varies widely and may include beef, pork, fish, or wild game, depending on local customs and availability.

The danger lies in consuming raw animal flesh that may harbor parasites or bacteria. In several documented outbreaks, raw wild boar larb has been linked to deadly infections caused by Streptococcus suis, as well as parasitic diseases such as trichinellosis. These infections can lead to fever, severe abdominal pain, neurological complications, and even death.

Eating raw meat of any kind carries inherent risks. Pathogens that are harmless to animals can become life-threatening once inside the human body, making larb a dish that demands caution and informed preparation.

Live octopus

In parts of Korea, live octopus dishes are considered a culinary experience. Although the animal is killed before serving, its tentacles may still move and retain active suction reflexes.

The primary risk is mechanical rather than toxic. The suction cups can attach to the tongue, throat, or airway while being swallowed, leading to choking. Several fatal incidents have been reported where individuals were unable to dislodge the tentacles in time.

Chewing thoroughly and cutting the tentacles into small pieces reduces risk, but it does not eliminate it entirely. This dish remains dangerous due to the unpredictability of the octopus’s reflexes.

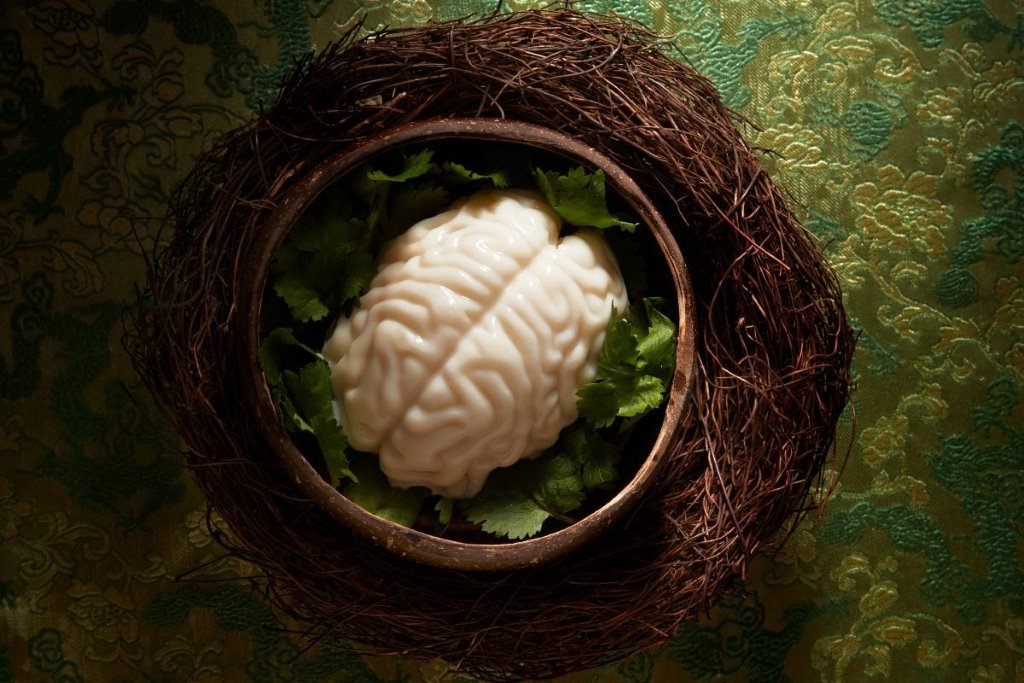

Monkey brains

Monkey brains are consumed in some regions as a rare and controversial delicacy. Beyond ethical concerns, the health risks associated with eating primate brain tissue are severe.

Consuming brain tissue can expose humans to prion diseases, including Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. These disorders are fatal, progressive, and untreatable, causing irreversible brain degeneration that leads to dementia and death.

Prions are resistant to heat and cooking, meaning preparation does not make the food safer. The extreme consequences make this one of the most dangerous foods on the planet.

Peanuts

For millions of people worldwide, peanuts are harmless and nutritious. For others, they are among the most dangerous foods imaginable. Peanut allergies are one of the most common and severe food allergies known.

Even trace amounts of peanut proteins can trigger anaphylaxis in sensitive individuals. Symptoms include swelling of the throat, difficulty breathing, a sudden drop in blood pressure, dizziness, and loss of consciousness. Without immediate treatment, reactions can be fatal.

Because reactions can occur from airborne particles or cross-contamination, peanuts are restricted in many schools and public spaces. The danger does not come from the peanut itself, but from the body’s immune response to it.

Pufferfish

Pufferfish, known as fugu in Japan, is one of the most infamous dangerous foods in the world. The fish contains tetrodotoxin, a neurotoxin far more lethal than cyanide.

This toxin is concentrated in the liver, ovaries, intestines, and skin. Even a tiny amount can cause paralysis, respiratory failure, and death. There is no antidote.

Because of this, only licensed chefs with years of specialized training are legally allowed to prepare pufferfish in Japan. Despite strict controls, poisoning cases still occur each year, underscoring how unforgiving this food can be.

Raw milk

Raw milk is milk that has not been pasteurized to kill harmful microorganisms. Advocates often claim it is more natural or nutritious, but from a food safety perspective, it carries well-documented risks.

Raw milk can contain dangerous bacteria such as Salmonella, Listeria monocytogenes, Campylobacter, and E. coli. These pathogens can cause severe gastrointestinal illness, bloodstream infections, miscarriages, and death, particularly in infants, pregnant women, the elderly, and people with weakened immune systems.

Pasteurization was introduced specifically to prevent these outcomes. While healthy adults may consume raw milk without immediate illness, the risk remains unpredictable and potentially severe.

Rhubarb leaves

Rhubarb stalks are widely used in desserts, but the leaves are highly toxic. They contain large amounts of oxalic acid and anthraquinone glycosides, compounds that interfere with calcium metabolism and kidney function.

Ingesting rhubarb leaves can cause nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, weakness, and difficulty breathing. Severe poisoning may lead to kidney failure, seizures, or coma. Cooking does not reliably destroy these toxins.

Because the stalks are safe while the leaves are dangerous, confusion during harvesting or food preparation can lead to accidental poisoning. For this reason, rhubarb leaves should never be eaten under any circumstances.

San-nakji (live octopus variant)

San-nakji is a Korean dish similar to live octopus, often served with freshly cut tentacles that are still moving due to nerve reflexes. While culturally significant, it presents a serious choking hazard.

The suction cups remain active even after the octopus has been killed. When swallowed improperly, they can adhere to the throat or airway, making breathing impossible. Several fatal incidents have been recorded involving this dish.

Proper preparation and careful chewing reduce risk, but they do not eliminate it. The danger lies in the mechanical behavior of the food rather than toxicity.

Star fruit

Star fruit is harmless to most people but extremely dangerous for individuals with kidney disease. It contains neurotoxins that are normally filtered out by healthy kidneys.

When these toxins accumulate, they can cause hiccups, vomiting, confusion, seizures, and coma. In some cases, exposure has been fatal even after small amounts of fruit or juice.

Because the fruit is widely available and often perceived as healthy, the risk is frequently overlooked. For people with impaired kidney function, complete avoidance is necessary.

Tuna (high mercury species)

Large tuna species such as bluefin, albacore, and yellowfin can accumulate high levels of mercury due to their long lifespan and position at the top of the marine food chain.

Mercury exposure affects the nervous system and is particularly dangerous for pregnant women and young children, as it can interfere with brain development. Symptoms in adults include memory problems, tremors, and impaired coordination.

Limiting consumption and choosing lower-mercury fish reduces risk. The danger comes from accumulation over time rather than a single meal.

Wild almonds

Wild almonds differ from commercially sold sweet almonds. They naturally contain amygdalin, a compound that breaks down into cyanide when metabolized.

Eating even a small number of bitter wild almonds can cause cyanide poisoning, leading to dizziness, nausea, rapid breathing, and in severe cases respiratory failure or death. Cooking does not reliably eliminate this risk.

Commercial almonds are bred to remove this compound, but wild varieties remain dangerous and should never be eaten.

Yam beans (jicama seeds)

Jicama roots are safe and widely eaten, but the seeds, leaves, and stems of the plant are toxic. They contain rotenone, a compound used as an insecticide.

Consuming the seeds can cause nausea, vomiting, muscle weakness, and respiratory distress. In high doses, rotenone is lethal.

Mistaking edible roots for other parts of the plant during preparation or foraging can lead to poisoning, making proper identification essential.

Yew berries

Yew trees produce berries that appear harmless, but almost every part of the plant is toxic. The seeds inside the berries contain taxine alkaloids that interfere with heart rhythm.

Ingesting yew seeds can cause dizziness, seizures, cardiac arrest, and sudden death. The red flesh of the berry is less toxic, but the risk of biting into the seed makes consumption extremely dangerous.

Yew poisoning has been documented in both humans and livestock, reinforcing its reputation as one of the most dangerous plants associated with food.

Across cultures, these foods illustrate how thin the line can be between nourishment and danger. In many cases, risk is controlled through knowledge, preparation, and tradition. When that knowledge is missing or ignored, food itself can become a serious threat.