When most people imagine prehistoric terror, their minds jump immediately to dinosaurs. Towering tyrannosaurs, horned giants, and thunderous herds dominate documentaries, books, and movies. Dinosaurs have become the public face of Earth’s violent past. But that focus hides a much broader and, in many cases, far more disturbing reality. Dinosaurs were only one chapter in a planet that has repeatedly produced creatures built to kill, dominate, and survive in brutally unforgiving worlds.

Long before dinosaurs appeared, evolution had already experimented with apex predators that hunted with speed, intelligence, and specialized weapons. After dinosaurs vanished, nature wasted no time filling the empty niches with new monsters. Some ruled the oceans with jaws capable of crushing whales. Others stalked land as mammal-like predators armed with saber teeth long before true mammals rose to prominence. The skies, too, were once claimed by flying creatures so large that their shadows alone would have inspired panic in anything below.

What makes these animals especially unsettling is how unfamiliar they feel. Dinosaurs, for all their size and danger, have become strangely comfortable through repetition. We know their names, their shapes, their habits. Many prehistoric animals outside that category, however, remain obscure, misunderstood, or underestimated. They don’t fit neatly into the dinosaur narrative, yet they were every bit as dominant—and in some cases, even more lethal.

Some of these creatures lived in environments that would feel alien today: oceans hotter than any modern sea, forests where oxygen levels supported colossal life forms, and ecosystems recovering from mass extinctions where only the most aggressive survivors thrived. Others lived in a world not so different from our own, hunting animals we still recognize, sharing landscapes that early humans would later walk.

This list focuses on prehistoric animals that were not dinosaurs but earned their reputation through size, power, behavior, and ecological dominance. These were not background creatures living in the shadow of dinosaurs. They were rulers of their own domains—on land, in the air, and beneath the waves. Understanding them doesn’t just expand our view of prehistory; it forces us to confront how often nature has produced nightmares far beyond anything alive today.

And perhaps most unsettling of all is this: many of these creatures disappeared not because they were weak or poorly adapted, but because Earth itself changed. If history has proven anything, it’s that when conditions are right, evolution is more than capable of creating monsters again.

Before and After Dinosaurs: The Scariest Prehistoric Creatures

Titanoboa

If the giant snakes of modern movies seem frightening, Titanoboa makes them look tame by comparison. This prehistoric serpent holds the title of the largest snake ever to exist, dwarfing today’s anacondas and pythons in every measurable way.

Titanoboa lived shortly after the extinction of the dinosaurs, filling ecological roles left vacant by vanished apex predators. Fossil evidence suggests it could grow over 40 feet long and weigh as much as 2,500 pounds. That puts it close to the weight of a giraffe, packed into a body built entirely for constriction and ambush.

Rather than relying on venom, Titanoboa would have killed by wrapping its massive coils around prey and crushing them with overwhelming force. Its size alone suggests it could take down large mammals and possibly even challenge young or weakened dinosaurs had their timelines overlapped. Some researchers speculate that Titanoboa occupied the top of its food chain with little competition, ruling tropical swamps and river systems with ease.

Its existence also provides clues about Earth’s ancient climate. Snakes of this size require extreme heat to survive, meaning the regions Titanoboa inhabited were significantly warmer than comparable environments today. In that sense, Titanoboa wasn’t just terrifying—it was a living indicator of a far more hostile prehistoric world.

A popular thought experiment often asks who would win in a confrontation between Titanoboa and Tyrannosaurus rex. While they never coexisted, the debate highlights just how formidable this snake truly was. Size, strength, and surprise would have made Titanoboa a nightmare opponent for almost anything that crossed its path.

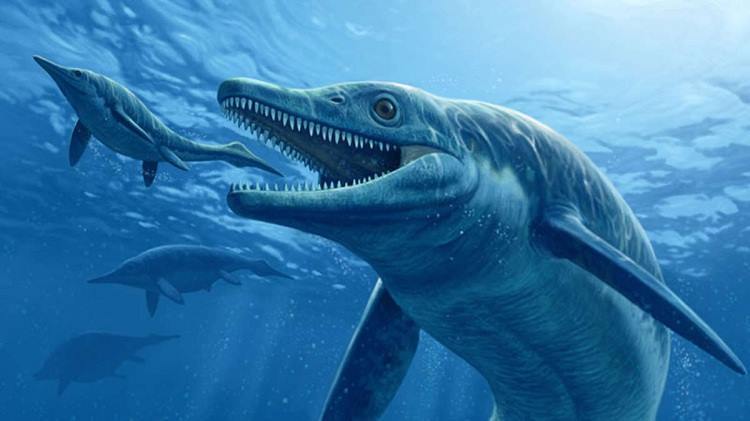

Liopleurodon

The ancient seas were far deadlier than modern oceans, and few creatures embody that danger better than Liopleurodon. Often mistaken for a dinosaur, Liopleurodon was actually a plesiosaur—a group of marine reptiles that dominated Jurassic waters.

Liopleurodon is widely regarded as one of the most dangerous ocean predators of its time. Estimates suggest it could reach lengths of over 30 feet and weigh more than 3,500 pounds. Its most terrifying feature was its skull, which was massive even by prehistoric standards and packed with long, powerful teeth designed to seize and tear apart prey.

Unlike many marine animals that relied on speed alone, Liopleurodon combined power with intelligence. Scientists believe it may have had an advanced sense of smell, allowing it to track prey over long distances. This would have made escape nearly impossible once it locked onto a target.

The Jurassic ocean was an unforgiving environment filled with giant fish, other marine reptiles, and early sharks. In that brutal ecosystem, Liopleurodon sat near the top of the food chain. Anything smaller than it was potential prey, and even similarly sized animals would have avoided direct confrontation.

Encounters with a creature like Liopleurodon would have been swift and violent. With a single bite, it could crush bone, disable prey, and end a hunt almost instantly. It wasn’t just a predator—it was an underwater executioner.

Sarcosuchus

Nicknamed “SuperCroc,” Sarcosuchus was not a true crocodile, but it was closely related. This massive reptile lived alongside dinosaurs and grew to sizes that make today’s crocodiles look small by comparison.

Sarcosuchus is estimated to have reached nearly 40 feet in length and weighed close to eight metric tons. Its skull alone was enormous, filled with long, interlocking teeth perfect for grabbing struggling prey. Unlike modern crocodiles, which primarily target animals at the water’s edge, Sarcosuchus likely hunted dinosaurs that wandered too close to rivers and lakes.

Fossil evidence suggests that Sarcosuchus spent much of its time lurking in shallow waters, waiting patiently for prey. When the moment came, it would explode from the water with terrifying speed, dragging victims into the depths. Its sheer size meant that even large dinosaurs were not safe.

Living during a time when survival depended on constant vigilance, Sarcosuchus represented a threat that could strike without warning. Its presence alone would have reshaped the behavior of animals living near waterways, turning rivers into zones of constant danger.

Mosasaurus

Mosasaurus was not a dinosaur, even though it’s often mistaken for one. It was a massive marine reptile that ruled the oceans during the late Cretaceous period, and it did so with overwhelming force. In its time, Mosasaurus was the undisputed apex predator of the seas.

Estimates suggest that some species reached nearly 60 feet in length. Its body was long and muscular, with powerful fins and a tail built for explosive speed. The head resembled that of a crocodile, but far larger, and its jaws were lined with conical teeth designed to grip slippery prey and prevent escape.

Unlike earlier marine predators, Mosasaurus had a flexible jaw structure that allowed it to swallow large prey whole or tear apart animals nearly its own size. Fossil evidence shows bite marks on other mosasaurs, suggesting that cannibalism may have occurred when food was scarce. Fish, turtles, ammonites, and even smaller marine reptiles all fell within its hunting range.

The dominance of Mosasaurus was so complete that few animals could challenge it. Its extinction coincided with the same catastrophic event that wiped out the dinosaurs, ending an era in which oceans were ruled by monsters no human could survive encountering.

Megalodon

Few prehistoric animals have captured the public imagination like Megalodon. This colossal shark is often compared to Tyrannosaurus rex in terms of cultural impact, but unlike T. rex, Megalodon’s prey included animals still alive today.

Megalodon is estimated to have reached lengths of up to 60 feet and weighed between 50 and 100 metric tons. Its jaws alone could span more than six feet wide, and its bite force exceeded anything found in modern oceans. Fossilized whale bones bearing massive bite marks provide clear evidence of its hunting methods.

Unlike modern great white sharks, which often target smaller prey, Megalodon specialized in large marine mammals. It likely attacked whales by crushing their fins and ribs, disabling them before delivering a fatal bite. This method required intelligence, patience, and enormous power.

Megalodon went extinct around 2.6 million years ago, possibly due to cooling oceans and declining prey populations. Its disappearance reshaped marine ecosystems, allowing smaller predators to rise. The fact that it hunted animals we still recognize today makes Megalodon especially unsettling—it lived in a world that feels uncomfortably close to our own.

Quetzalcoatlus

Quetzalcoatlus challenges everything people think they know about flight. Often mistaken for a dinosaur, it was actually a pterosaur, a group of flying reptiles that evolved separately. Quetzalcoatlus holds the title of the largest flying animal ever discovered.

With a wingspan estimated at around 35 feet and a body weight between 450 and 550 pounds, it was larger than many small aircraft. When standing on the ground, Quetzalcoatlus was as tall as a giraffe, towering over most animals in its environment.

Despite its size, evidence suggests it was capable of powered flight. Some scientists believe it used a powerful quadrupedal launch, vaulting itself into the air using both wings and hind limbs. Once airborne, it could glide for long distances, scanning the landscape for food.

Its exact diet remains debated. Some theories suggest it hunted small animals on land, using its long beak to snatch prey, while others propose it scavenged like modern vultures. Regardless of its feeding strategy, encountering a flying predator of this scale would have been terrifying for any animal on the ground.

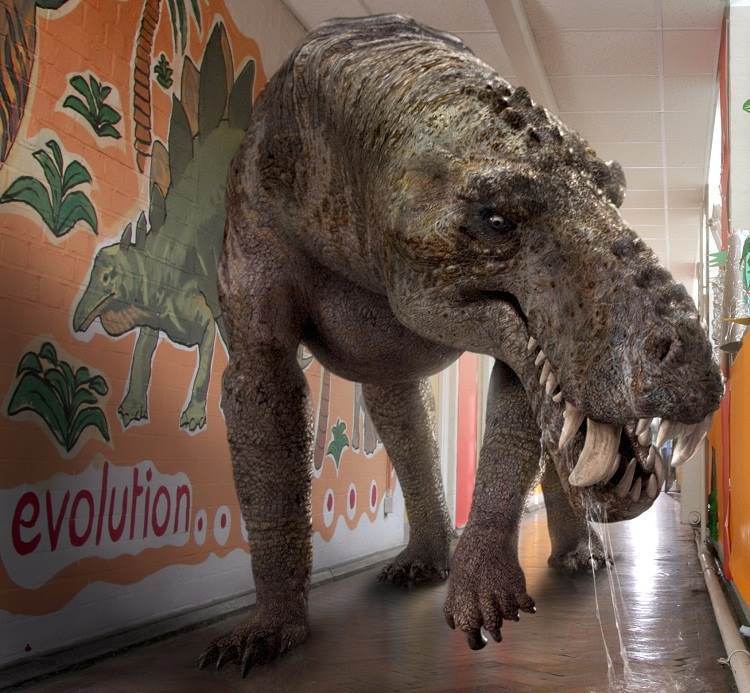

Gorgonops

Long before dinosaurs existed, Gorgonops ruled the land as one of the first true apex predators. Living around 260 million years ago during the Permian period, it belonged to a group of mammal-like reptiles that combined reptilian toughness with mammalian traits.

Gorgonops typically measured between six and ten feet in length, but what it lacked in size compared to later predators, it made up for in lethality. Its most striking feature was a pair of massive saber-like canine teeth that protruded from its upper jaw. These teeth were designed to deliver deep, fatal wounds.

Unlike slower herbivores of its time, Gorgonops was fast and agile. Its limb structure suggests it could run efficiently, making it capable of chasing down prey rather than relying solely on ambush. In a world filled with slow-moving animals, this advantage made it nearly unstoppable.

Gorgonops dominated its ecosystem until a massive extinction event wiped out most life on Earth. Its success marked an early chapter in the evolution of predators, setting the stage for the fearsome hunters that would follow millions of years later.

Phorusrhacidae

Phorusrhacidae, more commonly known as terror birds, were among the most unsettling predators ever to walk the Earth. These massive, flightless birds evolved in South America and dominated their environments for tens of millions of years after the extinction of the dinosaurs.

Terror birds ranged widely in size. Smaller species stood around three feet tall, while the largest reached heights of nearly ten feet. Built for speed, they could sprint at speeds estimated around 30 miles per hour, making escape nearly impossible for most prey. Their long, powerful legs were matched with a massive, hooked beak designed for crushing bone and delivering fatal blows.

Unlike birds that rely on talons, terror birds used their beaks as primary weapons. Paleontologists believe they struck prey repeatedly with downward blows, breaking bones and inflicting catastrophic injuries. Their skulls were reinforced to withstand these impacts, turning their heads into biological hammers.

For roughly 60 million years, terror birds sat near the top of the food chain in their ecosystems. Their closest modern relatives are birds like the seriema, which still retain some of the aggressive hunting behaviors of their prehistoric ancestors. Seeing a creature like Phorusrhacidae charging across open ground would have been a deeply frightening experience for any animal unlucky enough to be in its path.

Megatherium

At first glance, Megatherium might seem like an unlikely inclusion on a list of terrifying animals. As a giant ground sloth, it lacked the sharp teeth or claws typically associated with predators. But its sheer size and strength made it one of the most formidable mammals of the prehistoric world.

Megatherium was roughly the size of a modern elephant and could stand upright on its hind legs, using its massive tail as support. This posture allowed it to reach high vegetation, but it also made the animal appear far larger and more imposing than it already was. Its claws, some of the largest ever seen on a mammal, were capable of inflicting serious damage if the animal felt threatened.

While Megatherium is generally believed to have been a herbivore, some researchers suggest it may have been omnivorous, occasionally consuming meat or scavenging. Regardless of its diet, few predators would have risked attacking such a massive and well-armed creature.

Megatherium coexisted with early humans, and it likely played a role in shaping human behavior and migration patterns. Its extinction around 10,000 years ago coincides with the spread of human populations, though climate changes may have also contributed to its disappearance.

Thalattoarchon

Thalattoarchon is one of the more recent additions to the list of prehistoric terrors, having been identified by scientists in 2013. Its name translates roughly to “sea ruler,” an appropriate title for a creature that once dominated marine ecosystems.

Thalattoarchon was an ichthyosaur, a group of marine reptiles often compared to dolphins in shape, though far more dangerous. Measuring around 28 feet long, it was built for speed and power, with a streamlined body and enormous jaws filled with large, serrated teeth.

What sets Thalattoarchon apart from other marine predators is its position in the food web. It hunted other apex predators, placing it at the absolute top of its ecosystem. This level of dominance appeared relatively soon after a mass extinction event, showing how quickly nature can produce new monsters when ecological niches open up.

Fossil evidence suggests Thalattoarchon had a crushing bite capable of tearing apart large prey. Its discovery raises unsettling questions about how many other prehistoric predators remain undiscovered, hidden in layers of rock beneath our feet.

The prehistoric world was filled with animals that defy modern expectations of danger. Dinosaurs may dominate popular imagination, but these creatures prove that terror in Earth’s past came in many forms—on land, in the air, and beneath the waves.