Long before humans stood upright, before forests stretched across continents, and long before dinosaurs thundered across dry land, the oceans were already alive with astonishing predators. The sea, in fact, was Earth’s original battlefield. For hundreds of millions of years, it hosted creatures so strange and powerful that even today they feel almost fictional. Some had armor like tanks. Others had jaws designed like biological bear traps. A few grew larger than modern whales.

When we imagine ancient life, we often picture dinosaurs. But the truth is that the oceans were equally dramatic—sometimes even more brutal. From the Cambrian period to the late Cretaceous, prehistoric seas were ruled by creatures that shaped evolution itself. Let’s descend into those ancient waters and meet the rulers of the deep.

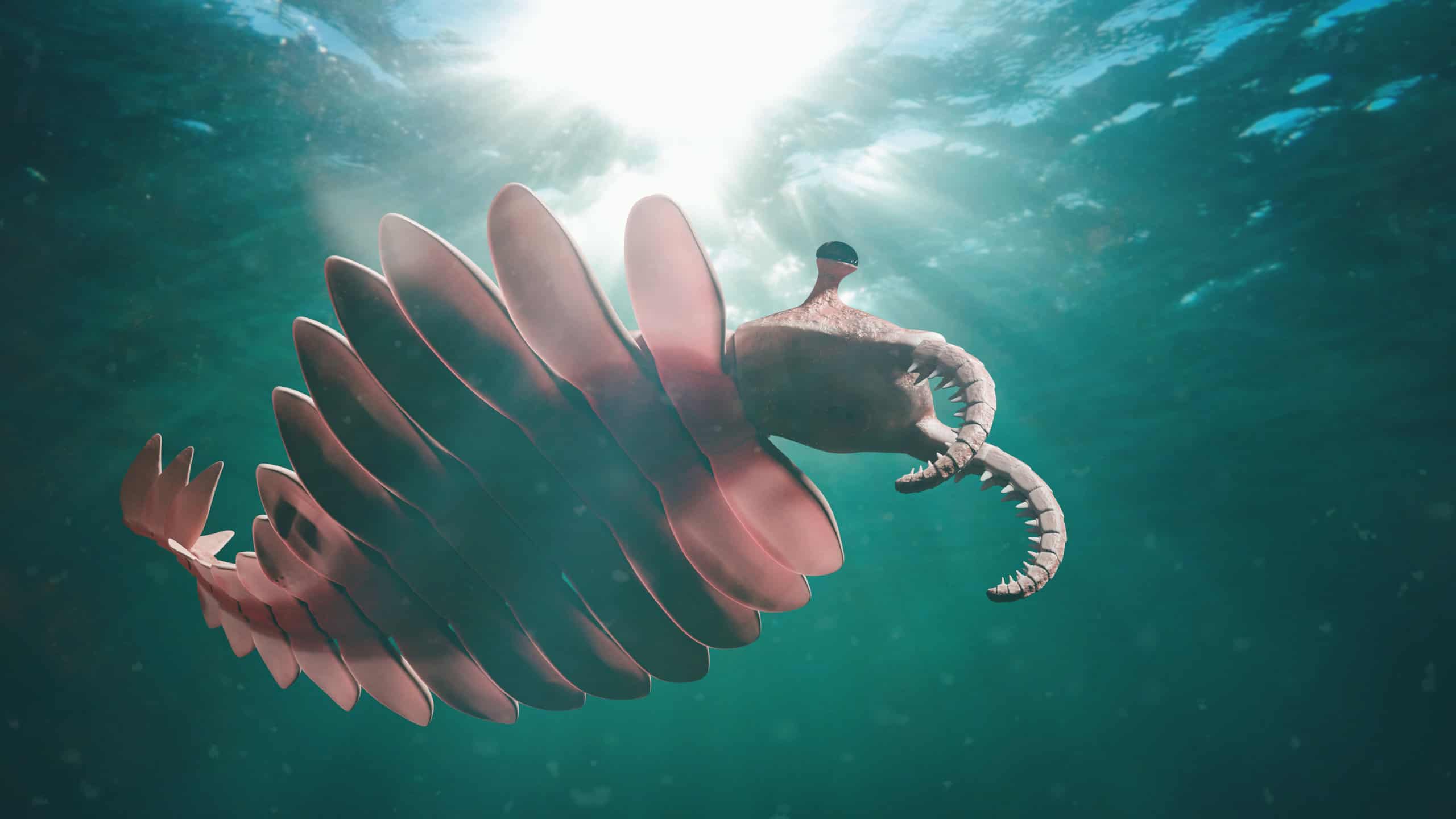

Anomalocaris – The Apex Predator of the Cambrian

Long before sharks or marine reptiles existed, a creature called Anomalocaris dominated the seas during the Cambrian period, roughly 500 million years ago.

At first glance, Anomalocaris doesn’t look like a typical predator. It had a segmented body, large compound eyes, and two spiny appendages extending from its head. But those appendages were the key to its dominance. They functioned like grasping claws, allowing it to seize prey with remarkable precision.

What made Anomalocaris extraordinary wasn’t just its size—about three feet long, enormous for its time—but its advanced vision. Its compound eyes were among the most sophisticated of any known Cambrian creature. That level of visual processing gave it a significant advantage in hunting.

Its circular mouth, lined with hard plates, could crush the armored trilobites that shared its environment. In a world just beginning to experiment with complex life, Anomalocaris represented a major evolutionary leap: speed, sight, and strategy combined into one efficient predator.

In many ways, it was the first true apex hunter of the oceans.

Dunkleosteus – The Armored Terror

Jump ahead roughly 350 million years to the Devonian period, and you’ll meet one of the most intimidating fish ever discovered: Dunkleosteus.

Dunkleosteus wasn’t just large—it was built like a living tank. Its head and upper body were covered in thick bony armor plates, giving it protection that few predators could penetrate. Unlike modern sharks, it didn’t have traditional teeth. Instead, it had sharpened bone plates that formed a powerful beak-like jaw.

Scientists estimate that Dunkleosteus could grow up to 30 feet long. Its bite force may have rivaled or exceeded that of modern great white sharks. When it closed its jaws, it created a slicing action capable of cutting through bone and armor alike.

But perhaps even more fascinating is how quickly it could strike. Evidence suggests its jaw mechanism allowed it to open its mouth extremely fast, creating a suction effect that pulled prey inward before they had time to react. In the murky Devonian seas, hesitation meant death.

Dunkleosteus ruled a time when vertebrates were just beginning to diversify. It was a glimpse of what predatory fish could become—stronger, smarter, and deadlier.

Pliosaurus – The Marine Reptile With Crushing Power

By the Jurassic period, reptiles had conquered the oceans. Among them, Pliosaurus stood out as one of the most fearsome.

Pliosaurus wasn’t a dinosaur, although it lived during the age of dinosaurs. It was a marine reptile with a massive head, powerful flippers, and jaws filled with conical teeth designed for gripping slippery prey.

Some species may have reached lengths of 40 feet. That alone is impressive, but its skull could measure over six feet long. Imagine encountering a creature whose head alone was longer than a human.

Its teeth weren’t for slicing—they were for holding and crushing. Pliosaurus likely preyed on other marine reptiles, large fish, and even smaller plesiosaurs. In an ocean already filled with competition, it carved out dominance through sheer size and jaw strength.

Its flippers allowed it to maneuver with surprising agility despite its bulk. It was not just a brute; it was an efficient swimmer capable of high-speed bursts when hunting.

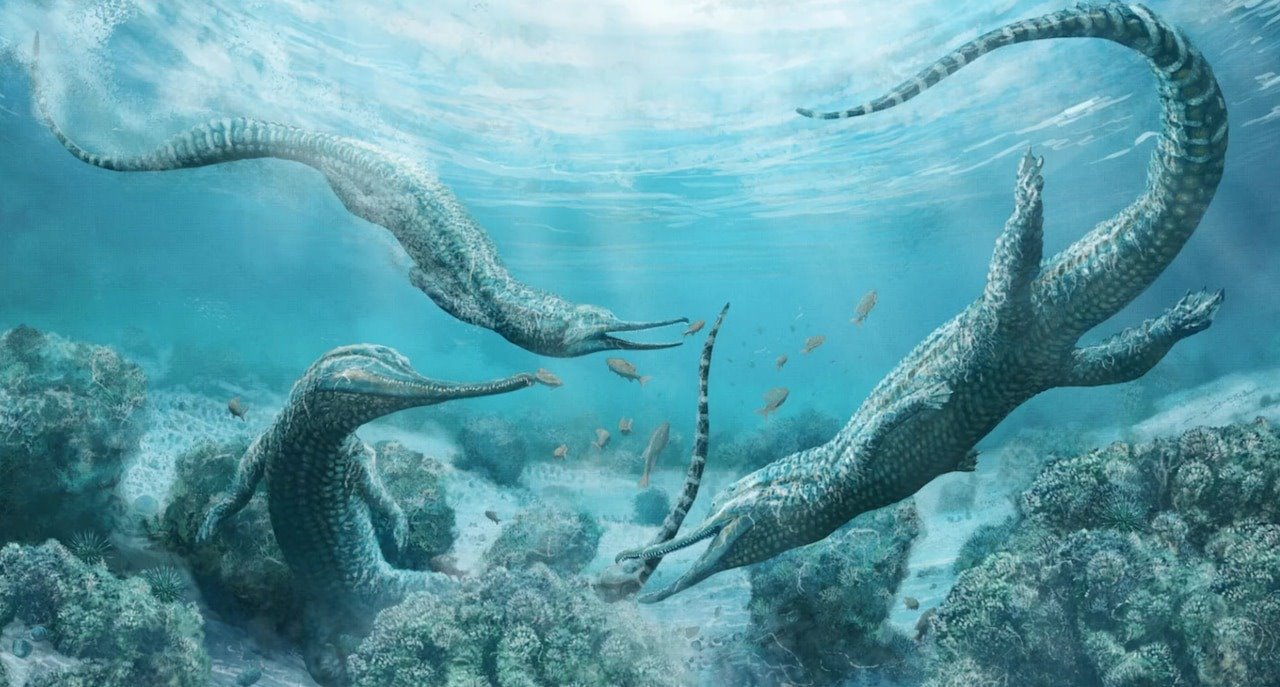

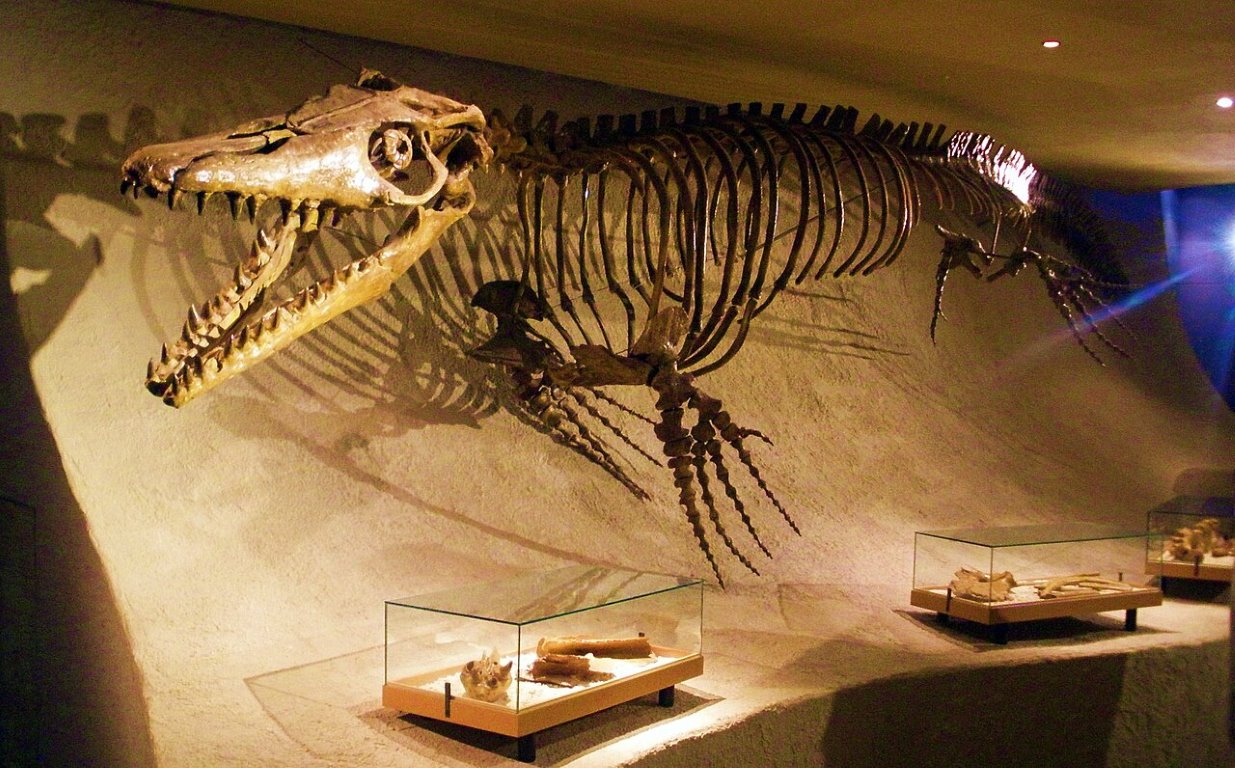

Mosasaurus – The Last Great Marine Predator of the Cretaceous

Toward the end of the Cretaceous period, just before the mass extinction that wiped out the dinosaurs, Mosasaurus emerged as one of the final rulers of prehistoric seas.

Mosasaurus was not a dinosaur either—it was more closely related to modern monitor lizards and snakes. But in the water, it evolved into something terrifying.

It could reach lengths of 50 feet or more. Its long, streamlined body ended in a powerful tail fin, allowing it to swim like a modern shark. Inside its mouth were rows of sharp, backward-curving teeth designed to prevent prey from escaping.

What’s particularly chilling is that Mosasaurus likely hunted almost anything it could overpower—fish, sea turtles, ammonites, and even other mosasaurs. Fossil evidence suggests it had a double-hinged jaw, similar to snakes, enabling it to swallow large prey whole.

In many ways, Mosasaurus represents the peak of marine reptile evolution. It ruled the oceans until the asteroid impact 66 million years ago ended its reign.

Megalodon – The Giant Shark That Redefined “Apex”

Millions of years after the marine reptiles vanished, another predator rose to dominate the oceans. It wasn’t armored like Dunkleosteus or reptilian like Mosasaurus. It was something far more familiar—yet far more extreme.

Megalodon.

Living roughly between 23 and 3.6 million years ago during the Miocene and Pliocene epochs, Megalodon was not just a big shark. It was likely the largest predatory shark to have ever lived. Estimates suggest it reached lengths of 50 to 60 feet, with some researchers arguing it may have grown even larger. Its teeth—some over seven inches long—are still found today, scattered across ocean floors and embedded in ancient sediments.

The scale of this animal is difficult to grasp. A modern great white shark looks impressive at 15 to 20 feet. Megalodon would have dwarfed it. Its bite force has been estimated to exceed 40,000 pounds per square inch, powerful enough to crush whale bones.

And that’s the key: Megalodon hunted whales.

Unlike earlier marine predators that fed primarily on fish or reptiles, Megalodon targeted large marine mammals. Fossilized whale bones bearing massive bite marks tell a clear story. It likely attacked from below, striking vital areas—fins, rib cages, and tails—crippling prey before finishing the kill. This strategy mirrors modern shark behavior but on a far more dramatic scale.

Its extinction remains debated. Climate shifts, declining prey populations, and competition from early killer whales may all have contributed. Whatever the cause, the disappearance of Megalodon reshaped ocean ecosystems permanently.

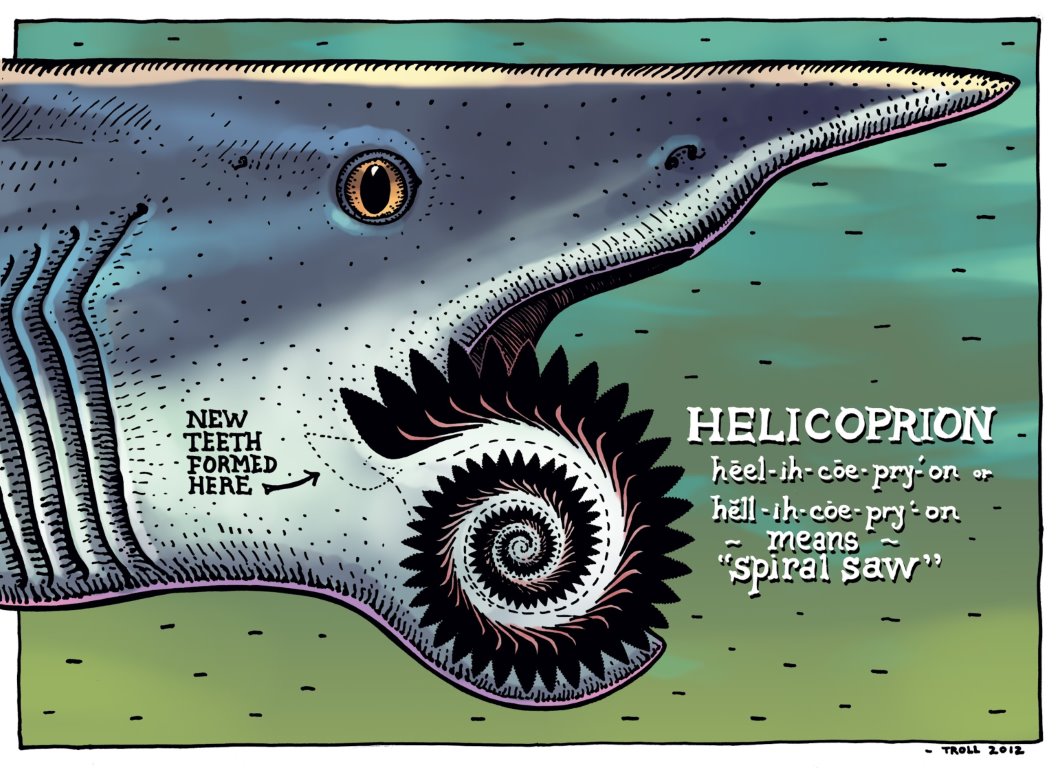

Helicoprion – The Shark With a Circular Saw

If Megalodon represents brute force, Helicoprion represents evolutionary experimentation.

Living around 290 million years ago during the Permian period, Helicoprion looked relatively shark-like—except for one astonishing feature: a spiral arrangement of teeth that resembled a circular saw.

For decades, scientists struggled to understand where this tooth “whorl” was located. Early reconstructions imagined it sticking out from the snout like a bizarre buzzsaw weapon. Modern imaging techniques finally revealed the truth. The spiral sat inside the lower jaw.

This unique structure functioned like a slicing conveyor belt. As the animal bit down, new teeth rotated forward, ensuring it always had sharp cutting surfaces. Rather than crushing prey, Helicoprion likely specialized in soft-bodied animals such as squid and ammonites. The spiral teeth would slice through flesh efficiently, minimizing escape chances.

It’s a reminder that prehistoric oceans weren’t just dominated by giants. They were laboratories of design. Some creatures optimized power; others optimized precision.

Helicoprion may not have been the largest predator of its era, but it was certainly one of the strangest—and perhaps one of the most specialized.

Eurypterids – The Sea Scorpions of Shallow Waters

Long before sharks ruled open waters, coastal shallows belonged to creatures that seem almost alien by today’s standards: eurypterids, often called sea scorpions.

These arthropods appeared more than 400 million years ago. Some species were small, only a few inches long. Others grew over eight feet in length, making them among the largest arthropods to ever exist.

Despite their nickname, they were not true scorpions, though they were related to modern arachnids. Their bodies were segmented and armored, with large pincers and paddle-like appendages for swimming. In murky coastal lagoons, they were formidable predators.

Unlike fast-swimming pelagic hunters, eurypterids likely relied on ambush tactics. Their compound eyes allowed them to detect movement in low visibility, and their claws could grasp and manipulate prey with precision. Some species may have even ventured briefly onto land, marking early steps toward terrestrial colonization by arthropods.

For millions of years, they thrived. But as jawed fish diversified and marine ecosystems grew more competitive, eurypterids gradually declined and eventually vanished.

Their story reflects a pattern seen repeatedly in evolutionary history: dominance is temporary.

Liopleurodon – The Powerhouse of the Jurassic Seas

Another marine reptile deserves mention when discussing prehistoric rulers of the ocean: Liopleurodon.

Often overshadowed by its relatives, Liopleurodon was one of the most powerful predators of the Middle to Late Jurassic seas. While popular media once exaggerated its size to absurd proportions, realistic estimates place it around 20 to 25 feet long—still enormous for its time.

What made Liopleurodon remarkable wasn’t just its size but its skull. Its head was proportionally massive, filled with thick, conical teeth ideal for gripping struggling prey. It likely hunted fish, smaller marine reptiles, and anything else within reach.

Its four strong flippers gave it speed and agility. Rather than cruising slowly, it was capable of sudden acceleration, closing distance rapidly during hunts. In a world filled with competition, that kind of mobility meant survival.

Liopleurodon exemplifies a pattern in prehistoric oceans: once a lineage discovered a successful body plan—large head, strong jaws, streamlined body—it refined it repeatedly.

Why the Oceans Produced Such Extreme Predators

It’s worth pausing to consider why prehistoric seas generated so many colossal hunters.

Water supports massive body sizes. Unlike land animals, marine creatures are buoyed by their environment. This allows them to grow larger without the skeletal limitations faced by terrestrial animals. Combine that with abundant food sources and vast hunting grounds, and you have the perfect conditions for evolutionary escalation.

There’s also the arms race effect. When prey evolves armor or speed, predators evolve stronger jaws or better vision. Over millions of years, this back-and-forth pushes species toward extremes.

Anomalocaris evolved better sight.

Dunkleosteus evolved crushing jaws.

Marine reptiles evolved speed and size.

Megalodon evolved unmatched bite force.

Each era had its champion, and each champion forced others to adapt or disappear.

The Real Legacy of These Ocean Rulers

It’s tempting to see prehistoric sea creatures as isolated marvels—monsters of the past that no longer matter. But their influence shaped modern marine life.

The predatory strategies of ancient sharks laid foundations for today’s apex fish. Marine reptiles demonstrated how land animals could return to water and thrive. Early arthropods experimented with body plans that influenced countless future species.

Even extinction events played a role. When one dominant predator vanished, it opened ecological space for another to rise. The fall of marine reptiles allowed large sharks to flourish. The disappearance of Megalodon reshaped whale evolution and predator-prey dynamics.

The oceans today feel calmer, perhaps less dramatic. But beneath the surface, echoes of those ancient rulers remain—in the streamlined bodies of sharks, in the hunting patterns of orcas, and in the vast, mysterious depths still largely unexplored.

If history teaches us anything, it’s this: the sea has always favored innovation, power, and adaptability. And for hundreds of millions of years, it belonged to creatures that perfected all three.

The depths have always had their kings.