Poison has always occupied a strange place in human history. Unlike weapons that rely on force or visibility, poisons work quietly, often invisibly, and sometimes slowly enough to blur the line between murder and natural death. For centuries, this made poisoning one of the most effective ways to kill without immediate suspicion. Long before modern toxicology existed, victims frequently died with symptoms that resembled common illnesses, leaving little evidence behind.

One of the most famous cases illustrating this ambiguity is that of Hawley Crippen, whose use of the poison hyoscine raised suspicion precisely because it was such an unusual choice. By the early twentieth century, the growing sophistication of forensic science meant that poisons were no longer as easy to hide. Chemical traces could be detected in tissue, bone, and even soil, making murder by poisoning increasingly risky. As a result, the method fell out of favor—not because it was ineffective, but because it had become detectable.

Despite this, poisoning was once far more common than historical records suggest. Many deaths attributed to fever, stomach illness, or unexplained collapse were almost certainly the result of toxic substances. Some poisons were widely available, sold openly as medicines, pesticides, or household products. Others were derived from plants and minerals that grew nearby or were traded casually across borders.

The poisons listed here are not chosen for shock value. They are substances that have repeatedly appeared in documented murder cases, assassinations, and unexplained deaths throughout history. Some act slowly, others kill within minutes, but all share one trait: when used with intent or ignorance, they are capable of ending a life with terrifying efficiency.

The Most Deadly Poisons Known to Humans

1. Arsenic

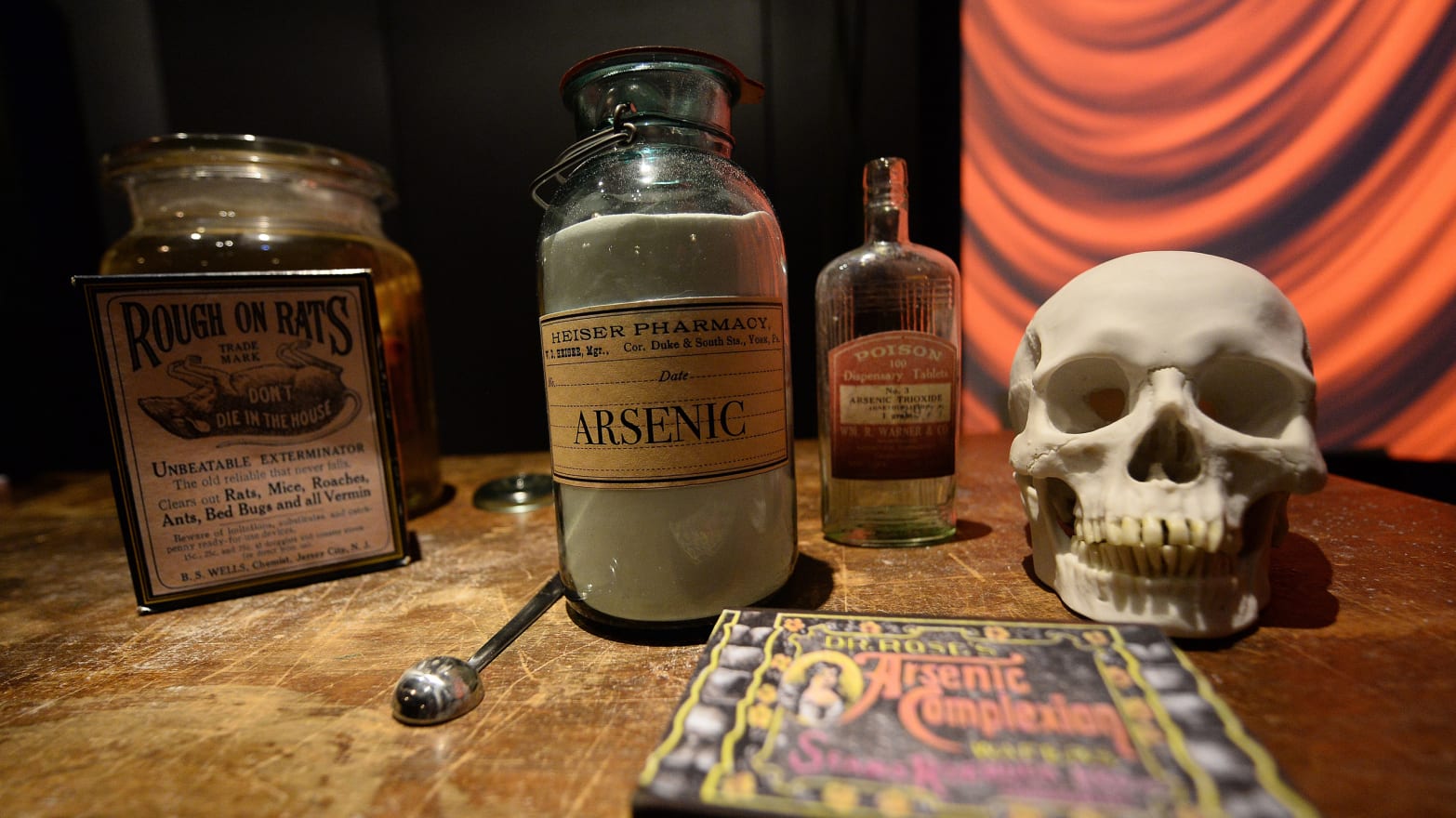

Arsenic has earned its reputation as the classic poison for good reason. Known and feared since Roman times, it was once considered almost perfect for murder. In its most common form, white arsenic or arsenic oxide, it is water-soluble, largely tasteless, and easy to mix into food or drink without detection.

For centuries, arsenic was readily available. It was produced as a by-product of copper and lead refining and sold openly for use in pest control. During the seventeenth century, a notorious poison known as “inheritance powder” was distributed by Toffana of Sicily, allegedly used to eliminate unwanted husbands. By the nineteenth century, arsenic could be found in homes across Europe and America, making it a frequent tool in domestic poisonings.

What made arsenic especially dangerous was how closely its symptoms mimicked common diseases of the time. Severe vomiting, diarrhea, and dehydration often resembled cholera or food poisoning. Victims could suffer for days before dying, and without chemical testing, doctors rarely suspected foul play. Today, arsenic is easily detected, but its long history as a silent killer remains unmatched.

2. Atropine

Atropine is derived from deadly nightshade, a plant known scientifically as Atropa belladonna. The name itself reflects its dual reputation: beautiful and lethal. In small doses, atropine can cause hallucinations, confusion, and altered perception. In larger amounts, it becomes fatal.

The poison was known in ancient Greece and later became a favored tool in Medieval Europe. A few berries from the nightshade plant can be enough to kill an adult, especially if ingested unknowingly. Atropine disrupts the nervous system, leading to rapid heartbeat, overheating, delirium, and eventually respiratory failure.

One reason atropine was so effective historically is that its effects closely resembled fevers and infections common in earlier centuries. Victims appeared to die of natural causes, and the plant itself grew wild in many regions, making access easy. Its combination of availability, potency, and plausible symptoms made it an attractive choice for poisoners for hundreds of years.

3. Strychnine

Strychnine is extracted from the seeds of the nux vomica tree and entered European awareness through trade with the Far East. Initially, it was prescribed in very small doses as a stimulant or tonic, a practice that would later be recognized as extremely dangerous.

The poison causes violent muscle contractions and extreme sensitivity to stimuli. Even small sounds or movements can trigger full-body convulsions. Death usually occurs through respiratory failure when the muscles involved in breathing become locked in spasm. There is no true antidote once severe symptoms begin.

Strychnine was also widely used as rat poison, making it easy to obtain. While relatively few domestic murders using strychnine are well documented, historians believe it was likely responsible for many unexplained deaths. Its dramatic symptoms may have discouraged some poisoners, but its effectiveness was undeniable.

4. Cyanide

Cyanide is often described as the fastest-acting poison known. It can be derived naturally from certain nut kernels and laurel leaves, but its most potent forms are industrial compounds such as sodium cyanide. Once ingested or inhaled, cyanide prevents cells from using oxygen, effectively suffocating the body from the inside.

Death can occur within minutes. Victims may experience dizziness, panic, convulsions, and cardiac arrest in rapid succession. Because of its speed, cyanide has been used both in assassinations and in suicide pills issued to spies who feared capture.

In modern history, cyanide gained notoriety through the 1980s Tylenol capsule poisonings, which resulted in multiple deaths and widespread panic. While tightly regulated today, cyanide remains one of the most feared poisons due to how little time it gives for intervention.

5. Thallium

Thallium was discovered in the 1860s and quickly gained a reputation as one of the most insidious poisons ever used. Thallium sulfate, in particular, is water-soluble, colorless, and tasteless—traits that once made it ideal for poisoning food and drink.

Unlike fast-acting poisons, thallium works slowly. Symptoms may not appear for days, allowing the poison to spread throughout the body before detection. Hair loss, nerve damage, and organ failure often follow, making diagnosis difficult until it is too late.

Thallium was once sold as rat poison in some countries and has been linked to both domestic murders and state-sponsored assassinations. Its delayed effects and lack of obvious early symptoms made it a favored tool of secret police organizations, including those under Saddam Hussein and the KGB.

6 Poisons That Have Been Used for Murder

Paracelsus, one of the early pioneers of toxicology, famously stated that “the dose makes the poison.” His point was simple but profound: nearly any substance can become lethal if enough of it enters the body. Water, salt, and even oxygen can kill under extreme conditions. What separates everyday chemicals from true poisons is not just toxicity, but how little is needed to cause irreversible harm.

Many substances classified as poisons have also served legitimate purposes. Some were used as medicines, others as cosmetics, pesticides, or industrial compounds. In certain contexts, their effects could be beneficial. In others, the same properties made them efficient tools for murder. The poisons in this section are notable not only for their lethality, but for how frequently they appear in historical records, legends, and documented criminal cases.

Belladonna or Deadly Nightshade

Belladonna, also known as deadly nightshade, is one of the most infamous poisonous plants in European history. Its name comes from the Italian phrase meaning “beautiful woman,” a reference to its use during the Middle Ages as a cosmetic. Women applied extracts of the plant to dilate their pupils, a look that was once considered attractive, despite the long-term damage it caused.

The plant contains several toxic compounds, including atropine, hyoscine, and solanine. These chemicals interfere with the nervous system, leading to confusion, hallucinations, rapid heartbeat, and loss of muscle control. In sufficient doses, belladonna causes respiratory failure and death. Both the berries and the leaves are highly toxic, and even small amounts can be fatal.

Historically, belladonna was used to poison arrows and eliminate enemies quietly. Roman legends describe its use in political assassinations, and it later entered folklore and literature, including references in works such as Macbeth. Its chemical relatives are still responsible for accidental poisonings today, particularly when solanine builds up in improperly stored potatoes.

Asp Venom

The use of snake venom as a poison has long captured the imagination, largely because of its association with Cleopatra. According to popular legend, the Egyptian queen ended her life using the bite of an asp. While dramatic, the reality of venom as a murder weapon is more complicated.

The asp is generally believed to have been the Egyptian cobra. Its venom contains a mix of neurotoxins and cytotoxins that attack nerve cells and tissue. Symptoms include nausea, paralysis, convulsions, and respiratory failure. Death is possible, but not guaranteed, and the bite itself is painful and unpredictable.

Using venom for murder presents practical challenges. Venom degrades quickly outside the snake, and dosing is difficult to control. These limitations make it less reliable than many chemical poisons. As a result, while snake venom appears frequently in literature and legend, its documented use in actual murders is relatively rare.

Poison Hemlock

Poison hemlock is one of the most historically significant plant poisons, known scientifically as Conium maculatum. Every part of the plant contains toxic alkaloids that interfere with nerve signaling. Once ingested, the poison causes progressive paralysis, beginning in the limbs and moving inward toward the respiratory muscles.

One of the most chilling aspects of hemlock poisoning is that the victim often remains fully conscious. The body slowly loses the ability to move and breathe while awareness remains intact. Death occurs through respiratory failure rather than loss of consciousness.

The most famous hemlock poisoning is the execution of Socrates in ancient Athens. According to Plato’s account in the Phaedo, Socrates calmly described the numbness spreading through his body as the poison took effect. That detailed description remains one of the earliest clinical observations of neurotoxic poisoning.

Strychnine

Strychnine appears again in this section because of its long history as both a medicine and a murder weapon. Extracted from the seeds of the Strychnos nux vomica tree, it was once prescribed in small doses to treat fatigue and digestive issues, despite its extreme toxicity.

The poison causes intense muscle spasms and hypersensitivity. Even slight stimuli can trigger violent convulsions. Victims often arch their backs and clench their jaws as breathing becomes impossible. Death results from asphyxiation due to paralysis of the respiratory muscles.

One of the most notorious figures associated with strychnine was Dr. Thomas Neil Cream, a nineteenth-century serial killer who used it to poison victims under the guise of medical treatment. While strychnine has largely been replaced by less dangerous substances in pest control, it still appears occasionally in illicit drugs and athletic doping, where accidental poisoning remains a risk.

Arsenic

Arsenic returns here not as repetition, but as reinforcement of its historical dominance among poisons. Chemically classified as a metalloid, arsenic disrupts essential enzyme systems in the body, shutting down cellular processes at a fundamental level.

Naturally present in soil and groundwater, arsenic exposure still affects millions worldwide through contaminated drinking water. Historically, it was used extensively in pesticides, pigments, and wood treatments. Its popularity in the Middle Ages stemmed from how closely its symptoms resembled common diseases.

Powerful families, including the Borgias, were rumored to use arsenic as a political tool, though not all claims are supported by evidence. What is certain is that arsenic poisoning became far more difficult to hide once reliable chemical tests were developed in the nineteenth century, marking the beginning of the end for poison as a common murder method.

Polonium

Polonium represents a modern evolution in poisoning. Unlike plant-based or mineral toxins, polonium is a highly radioactive element that kills through radiation rather than chemical interaction. It is lethal in astonishingly small quantities, making it one of the most dangerous substances ever discovered.

Once inside the body, polonium emits intense radiation that destroys tissue from within. Symptoms of radiation poisoning include nausea, hair loss, organ failure, and immune system collapse. There is no cure. Death typically occurs days or weeks after exposure, often after prolonged suffering.

The most famous case involving polonium was the poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko in 2006. Traces of polonium-210 were later found across multiple locations he had visited, highlighting both the substance’s lethality and its detectability. Earlier scientific exposure, including that of Irene Curie, demonstrated just how unforgiving radioactive poisons can be.

Poison as a method of killing has largely faded from everyday crime, not because it became less effective, but because science caught up with it. Modern forensic techniques can detect trace amounts of toxic substances in hair, bone, soil, and even decades-old remains. What once passed easily as illness is now far more likely to leave a chemical fingerprint. That shift has turned many classic poisons from perfect crimes into obvious ones.

Yet these substances have not disappeared. Many still exist in laboratories, industries, natural environments, and even homes. Some are regulated tightly, others occur naturally in plants, minerals, or animals that people may encounter without realizing the danger. In several cases, the poison itself is not illegal at all; it is the dose, exposure method, or misuse that turns it lethal.

What history makes clear is that poison does not need to act quickly to be effective. Some of the most feared toxins worked precisely because they delayed symptoms, confused diagnosis, or mimicked common diseases. Others killed so rapidly that intervention was impossible. From slow neurological shutdown to sudden respiratory collapse, poisons have exploited nearly every vulnerability of the human body.

Understanding these substances is not about fascination with death, but about recognizing how fragile the line between safety and danger can be. Many of the poisons discussed here were once everyday tools, medicines, or cosmetics. Others still exist quietly in nature, unchanged for centuries. Awareness, rather than fear, is what finally removed poison from its place as a common weapon—and it remains the only real defense against it today.