As temperatures rise and outdoor activity increases, encounters between humans and snakes become more common. Snakes that remain hidden during colder months begin to move again in spring and summer, searching for food and warmer ground. In many regions, this seasonal change leads to a noticeable increase in snakebite incidents, particularly among hikers, gardeners, campers, and people working outdoors.

Most snake encounters do not end in injury. Snakes generally avoid humans and bite only when they feel cornered, stepped on, or threatened. Still, when a bite does occur, it often creates panic and confusion. Many people are unsure whether the snake was venomous, how serious the bite may be, or what actions to take in the first critical moments. This uncertainty can lead to mistakes that worsen outcomes.

In the United States alone, thousands of people are bitten by venomous snakes each year. While fatalities are rare, venom can cause serious tissue damage, bleeding disorders, nerve disruption, and long-term complications if not treated properly. The good news is that modern medical care, when accessed quickly, is highly effective. Knowing what happens inside the body after a bite and understanding the correct response can make a significant difference in recovery.

Venom affects people differently depending on the snake species, the amount of venom delivered, the location of the bite, and how quickly treatment begins. Some bites inject no venom at all, while others deliver a dose strong enough to cause rapid swelling, internal injury, or breathing difficulties. Because the outcome is unpredictable, every suspected snakebite should be treated as a medical emergency.

This article explains what happens during a snakebite, how venom works, and what steps to take immediately after an encounter. The goal is not to create fear, but clarity. Calm, informed action saves tissue, prevents complications, and saves lives.

What to Do Immediately After a Snakebite

Understanding snake venom and how it works

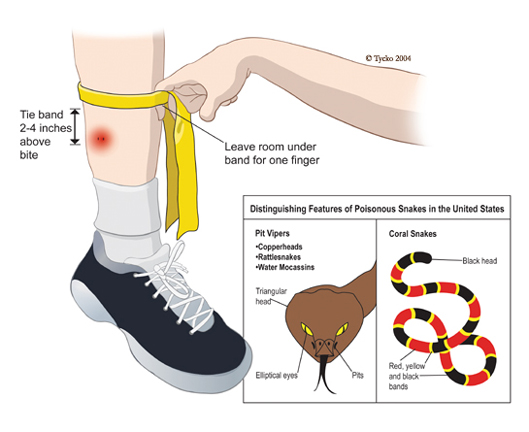

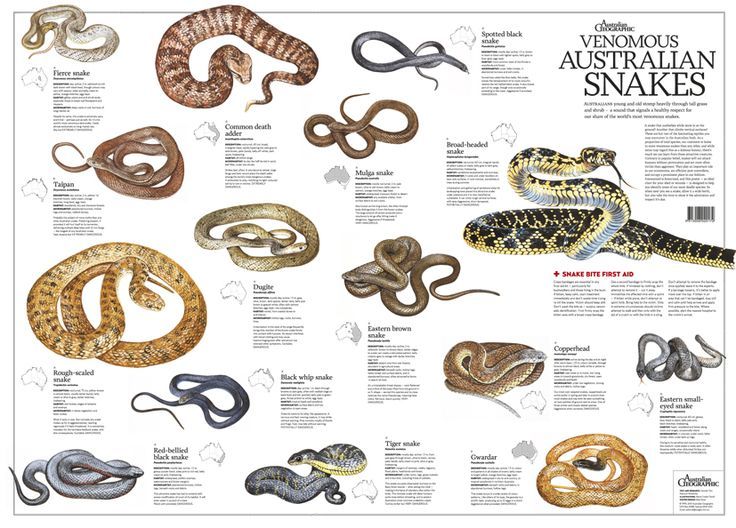

In the United States, venomous snakes fall into two primary groups: pit vipers and coral snakes. While they differ in appearance and venom composition, both are capable of causing serious injury. Pit vipers account for the majority of venomous bites, while coral snake bites are far less common but still medically significant.

Pit vipers share several physical traits. They typically have triangular-shaped heads, vertical pupils, and a heat-sensing pit located between the nostrils and eyes. This group includes rattlesnakes, copperheads, and cottonmouths. Rattlesnakes tend to deliver the most potent venom, while copperhead bites are often less severe but still painful and damaging. Cottonmouths are commonly found near water and may behave defensively if approached.

Coral snakes, by contrast, are slender and marked by bands of red, black, and yellow or white. Their venom works differently, targeting the nervous system rather than primarily damaging tissue. Coral snakes inject venom less frequently when they bite, but when venom is delivered, symptoms may be delayed and harder to detect at first.

Snakes control how much venom they release. Not every bite is venomous. Many pit viper bites are “dry,” meaning no venom is injected at all. In other cases, the amount released depends on how threatened the snake feels. A defensive bite may deliver less venom than one triggered by prolonged contact or pressure.

Venom itself is a complex mixture of proteins and enzymes. In pit vipers, these substances destroy tissue, interfere with blood clotting, and increase bleeding. This combination leads to swelling, pain, and internal damage around the bite site. Coral snake venom contains neurotoxins that disrupt communication between nerves and muscles, which can eventually affect breathing if untreated.

The effects of venom can begin quickly or develop over hours. Early treatment greatly reduces the risk of permanent injury. Understanding how venom behaves helps explain why movement, timing, and medical care are so important after a snakebite.

Immediate actions after a snakebite

The moments immediately following a snakebite are critical. Panic is natural, but remaining calm helps slow the spread of venom through the lymphatic system. The first priority is to move away from the snake to avoid additional bites. Snakes may strike again if they feel threatened, and attempting to capture or kill the animal increases the risk of further injury.

Once at a safe distance, the bitten person should limit movement as much as possible. Physical activity increases heart rate and blood flow, which can accelerate venom circulation. Sitting or lying down in a comfortable position reduces strain on the cardiovascular system. If possible, the bitten limb should be kept at or slightly below heart level to slow venom movement without cutting off circulation.

Remove any tight items near the bite area, such as rings, watches, bracelets, or tight clothing. Swelling can occur rapidly, and constricting objects may cause additional tissue damage as the area expands. Loosening footwear is also important if the bite is on the foot or ankle.

Calling emergency services or seeking immediate medical help should happen as soon as possible. Even if symptoms appear mild, venom effects can worsen over time. Do not wait for pain or swelling to increase before seeking help. Every suspected venomous bite should be treated as an emergency.

What not to do after a snakebite

Many traditional or movie-inspired remedies are ineffective or dangerous. Cutting the wound to “let venom out” does not work and increases the risk of infection, nerve damage, and bleeding. Venom spreads quickly through tissue and cannot be removed by surface cuts.

Suction devices, including mouth suction or commercial snakebite kits, do not remove meaningful amounts of venom. Studies show they provide little benefit while causing additional tissue injury. Applying ice or freezing the bite area can worsen tissue damage and does not neutralize venom.

Tourniquets should never be used. Restricting blood flow can lead to severe tissue death and increases the risk of losing a limb. Alcohol and caffeine should also be avoided, as they speed up circulation and worsen dehydration.

Electric shocks, herbal pastes, and folk remedies have no scientific basis and may delay proper treatment. The safest approach is simple: minimize movement, seek medical care, and avoid interventions that interfere with blood flow or wound healing.

Recognizing symptoms and warning signs

Snakebite symptoms vary depending on the species, venom type, and amount injected. Local symptoms often appear first and may include pain, swelling, redness, bruising, and bleeding at the bite site. Fang marks may be visible, but their absence does not rule out envenomation.

Systemic symptoms can develop over time. These may include nausea, vomiting, dizziness, weakness, sweating, blurred vision, and numbness around the mouth or limbs. In severe cases, victims may experience difficulty breathing, abnormal bleeding, confusion, or collapse.

Some venom effects are delayed. Coral snake bites, for example, may cause minimal early pain but lead to progressive nerve paralysis hours later. Because of this unpredictability, medical evaluation is essential even if symptoms seem mild at first.

Tracking changes in symptoms while waiting for help can be useful. Noting the time of the bite, progression of swelling, and appearance of new symptoms helps medical professionals make faster treatment decisions.

Medical treatment and antivenom

At a medical facility, healthcare providers assess the bite based on symptoms, bite location, and regional snake species. Blood tests may be used to evaluate clotting function, kidney performance, and muscle damage. Not every bite requires antivenom, but when it does, early administration significantly improves outcomes.

Antivenom works by binding to venom components and neutralizing their effects. Modern antivenoms are highly effective and much safer than older formulations. Allergic reactions are possible but closely monitored and treatable in hospital settings.

Supportive care is often required alongside antivenom. This may include pain management, wound care, intravenous fluids, and monitoring for complications such as infection or tissue damage. In severe cases, patients may require intensive care support.

Recovery time varies widely. Some people heal within days, while others experience weeks or months of swelling, stiffness, or nerve symptoms. Follow-up care ensures proper healing and identifies delayed complications.

Prevention and reducing future risk

Understanding snake behavior is one of the most effective ways to prevent bites. Wearing boots and long pants in snake-prone areas reduces the chance of fangs reaching skin. Using a flashlight at night, staying on clear paths, and avoiding tall grass or rocky crevices also lowers risk.

Never attempt to handle or provoke a snake, alive or dead. Even decapitated snakes can bite reflexively. Teaching children to recognize snakes and keep a safe distance is equally important.

While snakebites are frightening, most are survivable with calm action and timely medical care. Knowing what to do, what to avoid, and when to seek help turns a dangerous encounter into a manageable medical emergency rather than a life-threatening event.