Rocks and minerals are usually associated with stability, permanence, and value. They form the literal foundation of cities, industries, and technology. From smartphones and power grids to medical devices and jewelry, modern life depends heavily on substances pulled directly from the Earth. Because they feel solid and inert, minerals are rarely thought of as dangerous. Yet some of the most lethal substances known to humanity exist not as liquids or gases, but locked inside beautifully formed crystals and metallic ores.

Throughout history, humans have mined, handled, worn, and even consumed minerals without fully understanding their consequences. Entire civilizations used toxic minerals as pigments, medicines, cosmetics, and building materials. In many cases, the damage didn’t appear immediately. Illness developed slowly, symptoms were misunderstood, and deaths were blamed on unrelated causes. By the time the true danger was recognized, exposure had already become widespread.

What makes certain rocks and minerals especially dangerous is how subtle their effects can be. Some release toxic dust when disturbed. Others emit invisible radiation or deadly gases. A few dissolve in water, quietly poisoning ecosystems and living organisms without any obvious warning signs. Unlike venomous animals or corrosive chemicals, these minerals do not attack. They simply exist—and that is often enough.

Many of the deadliest minerals on Earth are also among the most visually striking. Brilliant blues, vivid yellows, metallic silvers, and deep reds disguise compounds capable of causing cancer, neurological damage, organ failure, or death. Their beauty has lured collectors, miners, artists, and workers into a false sense of safety for centuries.

This article examines the most dangerous rocks and minerals known to science—not hypothetical hazards, but naturally occurring substances that have caused real harm. Some are now heavily regulated or banned from use. Others still exist in homes, workplaces, and natural environments around the world. Understanding them is not about fear, but awareness. Because when danger comes from something as ordinary as a stone, ignorance is often the greatest risk of all.

The Most Dangerous Rocks and Minerals in the World

10 – Coloradoite

Coloradoite is a relatively rare crystalline mineral that forms within magma veins, where intense heat and pressure allow unusual chemical bonds to develop. At first glance, it appears unremarkable compared to more colorful gemstones, but its danger lies in its chemistry rather than its appearance.

This mineral is composed of mercury telluride, a compound formed when mercury fuses with tellurium. Each of these elements is highly toxic on its own, and together they create a mineral that poses a double threat. Mercury is notorious for its effects on the nervous system, while tellurium exposure can cause severe health complications, including respiratory distress and long-term organ damage.

Coloradoite becomes especially dangerous when disturbed. Heating, grinding, or chemically altering the mineral can release deadly vapor and fine dust, both of which are easily inhaled. Even brief exposure to these byproducts can lead to serious poisoning. Because of this instability, handling Coloradoite without protective equipment is extremely risky.

Despite its hazards, Coloradoite may be mined for its tellurium content. Tellurium has industrial value and is sometimes associated with gold-bearing minerals. In an ironic twist of geological history, the town of Kalgoorlie in Australia experienced a gold rush after it was discovered that gold-rich tellurides had been unknowingly used to fill potholes in the streets. What appeared worthless and dangerous at first turned out to be unexpectedly valuable—though still toxic.

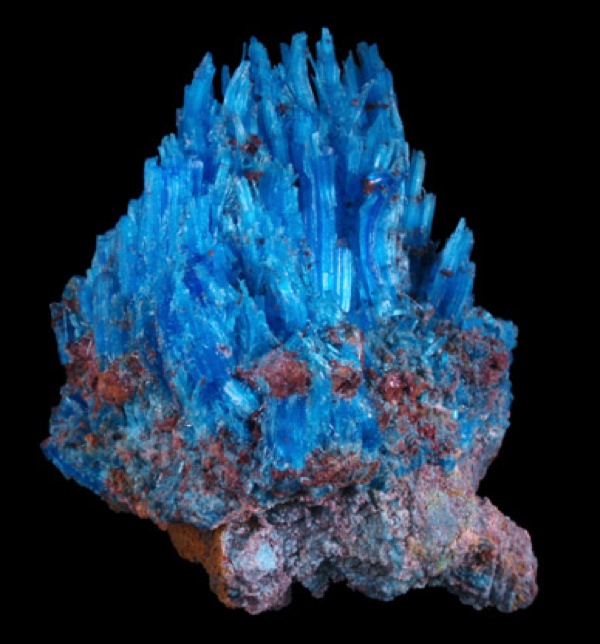

9 – Chalcanthite

Chalcanthite is instantly recognizable by its vivid blue crystals, which appear almost artificial in their intensity. The mineral’s beauty is one of the reasons it’s so dangerous. Composed primarily of copper sulfate combined with water, chalcanthite turns copper—an element essential to human biology in small amounts—into a lethal threat.

The key danger lies in bioavailability. Chalcanthite is water soluble, meaning its copper content can be absorbed rapidly and in large quantities by living organisms. Once inside the body, excess copper interferes with vital biological processes, weakening tissues and eventually shutting down organ systems. Plants and animals exposed to dissolved chalcanthite can die quickly.

Because it resembles certain salts, chalcanthite has caused serious poisonings when handled by inexperienced collectors or amateur scientists. Taste testing, even in tiny amounts, can result in a severe copper overdose. Environmental damage has also been documented. Simply releasing chalcanthite crystals into water has wiped out entire ponds of algae, demonstrating how destructive it can be outside controlled settings.

Its rarity and striking appearance have also fueled a niche market for artificial crystals. Some specimens sold to collectors are deliberately grown in laboratories and passed off as natural chalcanthite. While artificial versions may lack the same toxicity, genuine samples remain a serious hazard and should never be handled casually.

8 – Hutchinsonite

Thallium has often been described as the darker, more dangerous twin of lead. Similar in atomic weight but far more lethal, thallium appears in nature through rare and highly toxic mineral compounds. Hutchinsonite is one of the most dangerous examples ever identified.

This mineral is a complex mixture of thallium, lead, and arsenic—three of the most poisonous metals known to science. Each element brings its own risks, but together they form a lethal combination capable of causing severe illness or death through even limited exposure. Thallium poisoning is especially insidious, as it can be absorbed through the skin and often produces delayed symptoms.

Exposure to thallium compounds has been associated with hair loss, neurological damage, organ failure, and fatal outcomes. Hutchinsonite crystals concentrate these dangers into a visually dramatic mineral that should only ever be handled under controlled laboratory conditions.

Named after John Hutchinson, a respected mineralogist from Cambridge University, Hutchinsonite is most commonly found in mountainous regions of Europe, particularly within ore deposits. Its discovery helped highlight just how hazardous certain naturally occurring minerals can be, even when they form deep underground and remain unseen for centuries.

7 – Galena

Galena is the primary ore of lead and one of the most recognizable minerals ever extracted from the Earth. Its metallic silver-gray color and sharply defined cubic crystals give it an almost artificial appearance, as if it were machined rather than naturally formed. That visual perfection hides a long history of human harm.

Although lead is typically soft and malleable, galena behaves very differently due to its sulfur content. The mineral is brittle and fractures cleanly along cubic planes, meaning that when it breaks, it produces fine dust rather than bending or deforming. That dust is where the real danger lies. Lead particles can be inhaled or absorbed through contact, accumulating in the body over time.

For miners and industrial workers, galena exposure has historically resulted in widespread lead poisoning. Neurological damage, kidney failure, developmental disorders, and chronic illness have all been linked to prolonged contact with lead-bearing minerals. Even amateur collectors are not immune. Handling galena specimens without proper protection can transfer lead dust to the hands, which may later be ingested unintentionally.

Beyond direct exposure, galena poses environmental risks during extraction and processing. Once removed from the ground, separating lead from the ore releases contaminants into soil and water, affecting surrounding ecosystems. Despite its dangers, galena has played a central role in human technological development, a reminder that progress has often come at a steep biological cost.

6 – Asbestos

Chrysotile and Amphibolite

Asbestos stands apart from many other toxic minerals because its danger is not primarily chemical, but mechanical. Unlike substances that poison through ingestion or contact, asbestos causes harm by physically damaging the lungs at a microscopic level.

Asbestos is a naturally occurring group of fibrous minerals composed mainly of silica, iron, sodium, and oxygen. These minerals form long, thin fibers that can easily become airborne when disturbed. Once inhaled, the fibers embed themselves deep in lung tissue, where the body cannot effectively remove them.

Over time, these trapped fibers cause chronic irritation and scarring. This process can lead to severe respiratory diseases, including asbestosis, lung cancer, and mesothelioma. The carcinogenic effects are slow and cumulative, often taking decades to become apparent. This delayed onset made asbestos particularly dangerous, as many people were exposed long before the risks were fully understood.

Asbestos deposits can occur naturally among ordinary silica rocks, meaning exposure is not limited to industrial settings. Weathering can release fibers into the environment, and trace amounts of asbestos are now found throughout the atmosphere. As a result, many people unknowingly carry asbestos fibers in their lungs, even without direct occupational exposure.

5 – Arsenopyrite

Arsenopyrite is often called fool’s gold, but confusing it with gold is only one of the many mistakes people can make when encountering this mineral. Composed of arsenic, iron, and sulfur, arsenopyrite is among the most dangerous minerals a person might encounter in the wild.

The real threat emerges when the mineral is disturbed. Heating, crushing, or chemically altering arsenopyrite releases arsenic vapors that carry a strong garlic-like odor. These fumes are highly toxic, corrosive, and carcinogenic. Inhaling even small amounts can result in serious health consequences.

Handling arsenopyrite is risky even without visible alteration. Contact with the mineral can expose the skin to unstable arsenic compounds that may be absorbed into the body. Historically, arsenic exposure has been associated with organ failure, neurological damage, and increased cancer risk.

Interestingly, arsenopyrite can sometimes be identified by striking it with a hammer. As the mineral fractures, the brief release of arsenic produces a noticeable garlic smell. While this property has been used as a field test by geologists, it underscores just how dangerous casual interaction with the mineral can be.

4 – Torbernite

Torbernite is one of the most visually striking and quietly dangerous minerals on Earth. Its bright green, prism-shaped crystals form as secondary deposits in granitic rocks and are composed primarily of uranium combined with phosphorus, copper, water, and oxygen.

The danger of torbernite comes from both radiation and gas. As the uranium within the crystal decays, it releases ionizing radiation along with radon gas, a colorless, odorless substance known to cause lung cancer. These emissions occur slowly but continuously, turning even small specimens into persistent health hazards.

Collectors have historically been drawn to torbernite because of its vivid color and unusual crystal shapes. Many have unknowingly displayed radioactive samples in homes or museums, exposing themselves to prolonged low-level radiation. The mineral can also occur in granite, meaning trace amounts may exist in stone countertops or building materials.

Despite its risks, torbernite played an important role in early uranium prospecting. Bright green crystal blooms were used as visual indicators of uranium-rich deposits, guiding exploration during the early days of nuclear research.

3 – Stibnite

Stibnite is one of those minerals that looks deceptively refined. Its long, metallic-gray crystals form sharp, spear-like clusters that resemble polished steel rather than something pulled from the ground. That appearance once made it attractive for practical use, a decision that proved dangerous long before modern toxicology understood why.

The mineral is composed primarily of antimony sulfide. Antimony is a toxic element that interferes with many of the body’s basic biological processes, especially when ingested or inhaled over time. Historically, stibnite was used to manufacture utensils, cups, and even cosmetic products, a practice that led to repeated cases of unexplained illness and food poisoning.

When acidic foods or liquids came into contact with antimony-based containers, toxic compounds leached into meals. Chronic exposure caused symptoms ranging from nausea and vomiting to organ damage. Eventually, its use in household items was abandoned, but not before countless people suffered the consequences.

Handling stibnite specimens today still requires caution. The crystals are brittle, and fine dust can be released if they break or are scraped. While the mineral is visually impressive—especially specimens from Japan known for their dramatic, cathedral-like formations—it remains a substance best admired behind protective barriers rather than touched.

2 – Orpiment

Orpiment is one of the most beautiful and dangerous minerals ever used by humans. Its bright yellow-orange crystals are visually striking, almost glowing under light, which historically made it highly desirable for pigments and decorative use. That beauty comes at an extreme cost.

Chemically, orpiment is an arsenic sulfide mineral. Arsenic is infamous for its toxicity, and in orpiment, it exists in a form that can easily become airborne as fine powder. Inhalation or accidental ingestion can cause severe neurological damage, organ failure, and cancer.

Orpiment has a long and grim history. It was used in ancient times to poison arrows and enemies, and later ground into pigments for paintings and manuscripts. Artists working with orpiment-based paints often suffered mysterious illnesses, as arsenic dust accumulated in their bodies over years of exposure.

The mineral is sensitive to light and heat, which can cause it to degrade and release arsenic compounds more readily. A faint garlic-like odor sometimes accompanies disturbed samples, a warning sign of arsenic release. Despite being well-known for its dangers today, orpiment remains a tempting hazard due to its intense color and rarity.

1 – Cinnabar

Cinnabar stands at the top of the list for a reason. As the primary ore of mercury, it has caused more death, disease, and environmental destruction than perhaps any other mineral known to humanity. Its deep red coloration made it desirable across cultures, even as it silently poisoned those who handled it.

Formed in volcanic regions, cinnabar consists of mercury sulfide. When disturbed, crushed, or heated, it releases mercury vapor, one of the most dangerous forms of mercury exposure. Inhaled mercury vapor quickly crosses into the brain, causing tremors, memory loss, loss of sensation, and eventually death in severe cases.

Historically, cinnabar mining was effectively a death sentence. Miners exposed to mercury vapors suffered rapid neurological decline, earning mercury the nickname “madman’s poison.” Entire mining communities were devastated by chronic exposure long before protective measures existed.

Despite its toxicity, cinnabar was widely used for ornamental purposes and even traditional medicine, particularly in ancient China. Red pigments derived from cinnabar adorned temples, tombs, and artwork, while powdered forms were mistakenly believed to offer healing benefits. In reality, prolonged exposure often led to irreversible harm.

Today, cinnabar remains a powerful reminder that natural beauty can mask lethal danger. The mineral’s legacy is written not just in geology textbooks, but in centuries of human suffering caused by misunderstanding the risks hidden within the Earth itself.