When most people picture prehistoric predators, they imagine open landscapes — vast plains where massive dinosaurs chased prey across dry ground. But some of the most dangerous hunting grounds in Earth’s history were not on land at all. They were in slow-moving rivers, flooded forests, and steaming swamps where visibility was low and footing was uncertain.

Wetlands are unique environments. Water bends light, muffles sound, and hides movement. Mud absorbs footsteps. Dense vegetation breaks up silhouettes. In such places, the rules of hunting change completely. Speed becomes less important than patience. Teeth matter, but positioning matters more. A predator doesn’t need to chase when it can wait.

Throughout the Permian, Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous periods — and even into the age of early mammals — rivers and swamps repeatedly produced specialized hunters. Some were amphibians that lurked in shallow water long before dinosaurs appeared. Some were crocodilian giants that could drag multi-ton prey beneath the surface. Others were semi-aquatic dinosaurs built to move comfortably between land and water, exploiting both worlds.

What ties these animals together is not just habitat. It’s strategy.

They hunted where prey gathered to drink.

They attacked where escape routes were limited.

They used murky water as camouflage.

In wetlands, the surface often looks calm. That illusion has existed for hundreds of millions of years.

To step into a prehistoric riverbank was to enter a layered ecosystem — one where danger might be inches below the surface, disguised by reeds and shadow. These predators did not need long pursuits or dramatic chases. They relied on proximity, concealment, and explosive force delivered at exactly the right moment.

And in ancient swamps, that was more than enough.

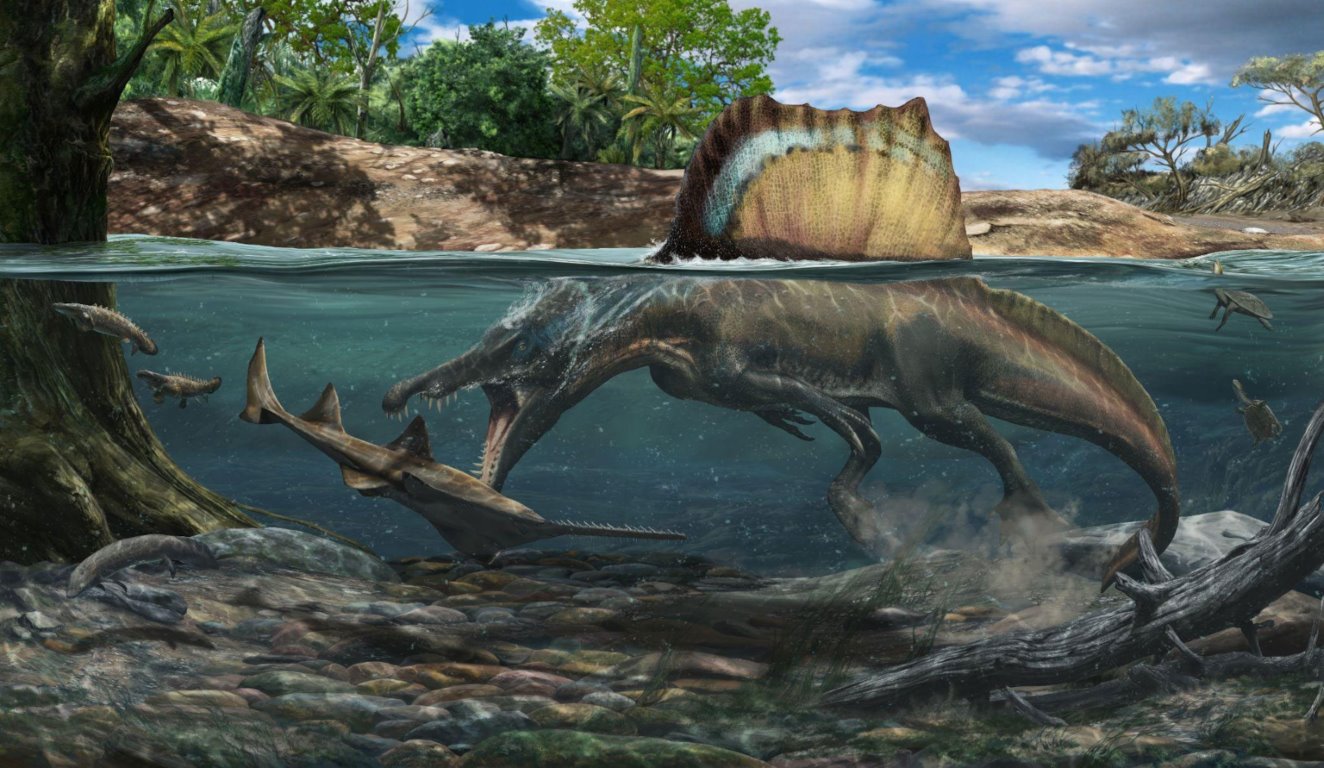

Spinosaurus — The Riverbank Giant

Few prehistoric predators are as closely associated with rivers as Spinosaurus.

Unlike most large theropod dinosaurs, Spinosaurus showed clear adaptations for a semi-aquatic lifestyle. Fossil evidence reveals dense bones that helped with buoyancy control, a long crocodile-like snout filled with conical teeth ideal for gripping slippery prey, and possibly even a paddle-like tail suited for propulsion.

Its skull shape resembles modern gharials more than typical land predators. That long snout allowed for quick snapping motions into water, minimizing splash and resistance. The teeth weren’t built for slicing flesh off large herbivores — they were built to grab and hold.

Spinosaurus likely hunted large fish in river systems across what is now North Africa. But fish were probably not its only target. Smaller dinosaurs venturing too close to water could have faced sudden ambush.

What makes river hunters terrifying is not their speed. It’s their invisibility. A partially submerged predator with only eyes and nostrils above the surface is almost undetectable.

In Cretaceous wetlands, the shoreline was not a safe place.

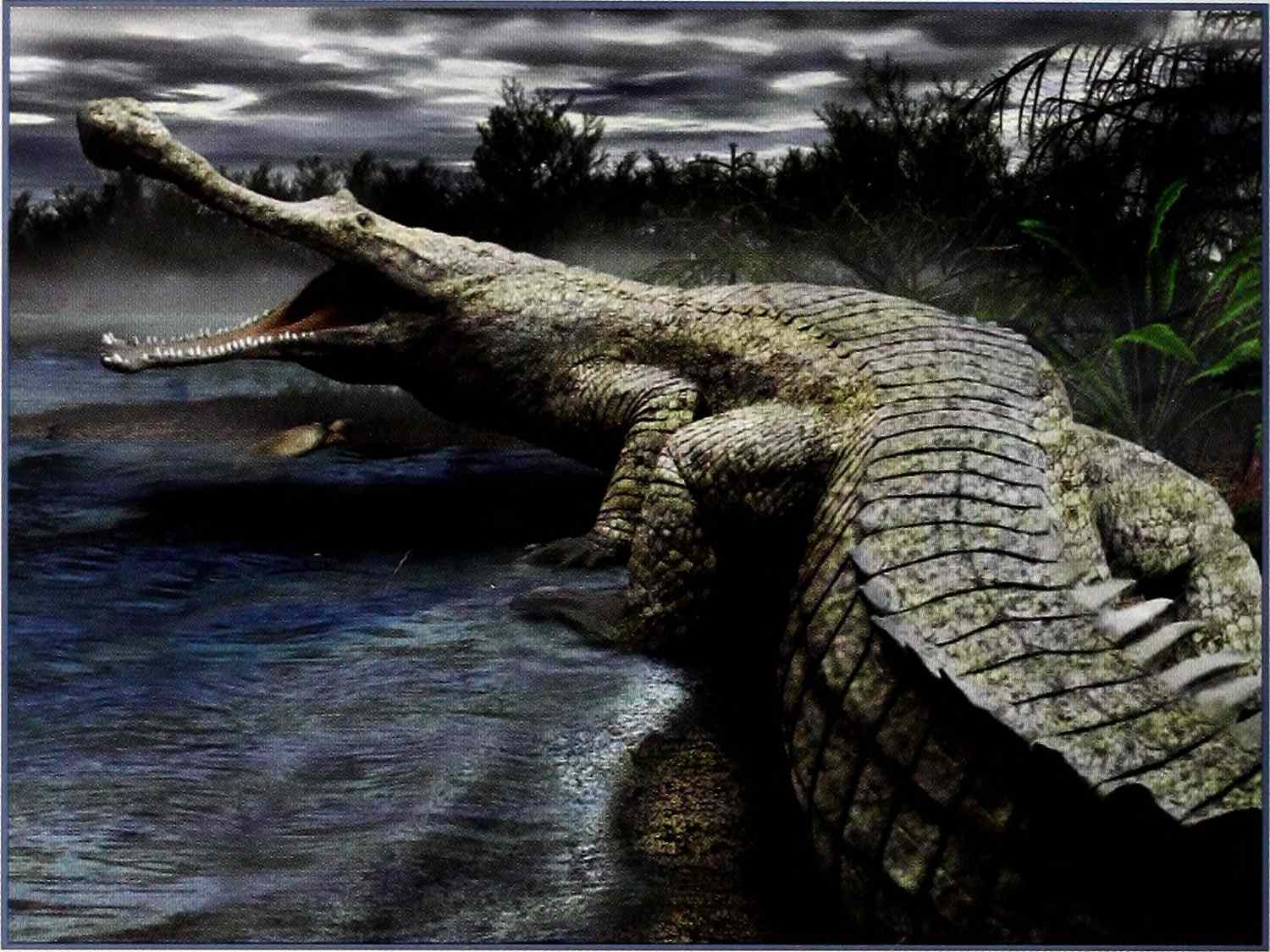

Sarcosuchus — The SuperCroc of Ancient Rivers

If Spinosaurus dominated the shoreline, Sarcosuchus dominated the water itself.

Often nicknamed “SuperCroc,” Sarcosuchus grew up to 30–40 feet long. Its body resembled modern crocodilians but on a massive scale. Thick armored skin embedded with osteoderms protected its back, while its elongated snout was packed with sharp teeth designed for gripping.

Like modern crocodiles, Sarcosuchus likely used ambush tactics. It would remain submerged, waiting near river crossings or shallow banks where prey gathered.

Once a target approached, it would launch upward in explosive motion, clamping down with powerful jaws. The strength of crocodilian bite mechanics even today is immense. Scaled to Sarcosuchus’s size, that force would have been devastating.

After the initial grab, drowning becomes the strategy. Prey dragged into deeper water quickly lose advantage.

Rivers don’t just hide predators. They give them leverage.

Deinosuchus — The Dinosaur Snatcher

Another prehistoric crocodilian, Deinosuchus, lived in North America during the Late Cretaceous.

Unlike Sarcosuchus, Deinosuchus coexisted directly with large dinosaurs. Fossilized dinosaur bones bearing massive bite marks have been attributed to it. That suggests this predator didn’t limit itself to fish.

Deinosuchus likely targeted dinosaurs that came to drink or cross waterways. With a body length reaching around 35 feet, it was capable of overpowering mid-sized dinosaurs.

Imagine a herd approaching a calm river. The surface barely moves. A sudden eruption of water. A juvenile dinosaur disappears beneath the surface.

Predation in swamps doesn’t always look dramatic. Often, it’s over before the rest of the herd understands what happened.

Baryonyx — The Fish Specialist

Closely related to Spinosaurus, Baryonyx provides strong evidence of river-based hunting.

A famous fossil specimen was discovered with fish scales preserved in its stomach region. That’s rare direct evidence of diet.

Baryonyx had long, narrow jaws filled with conical teeth — perfect for seizing fish. Its large claw on the forelimb may have been used to hook prey or stabilize struggling animals.

Unlike fully aquatic predators, Baryonyx likely hunted from the water’s edge or waded into shallow river systems.

Its build suggests a transitional hunter — comfortable near water, but still capable on land.

In swamps and floodplains, flexibility is survival.

Koolasuchus — The Amphibian Ambush Hunter

Not every swamp predator was a reptile. During the Early Cretaceous in what is now Australia, a massive amphibian called Koolasuchus hunted in cold, river-fed wetlands.

Koolasuchus belonged to a group of ancient amphibians known as temnospondyls. Unlike modern frogs or salamanders, this creature could reach lengths of around 15 feet. Its head was broad and flat, lined with sharp teeth suited for gripping slippery prey.

Its hunting style likely resembled that of modern giant salamanders — lying motionless in shallow water, blending into muddy riverbeds, waiting for fish or small reptiles to drift close.

Because it lived in cooler climates where crocodilians were rare, Koolasuchus filled the top aquatic predator role in its environment.

Amphibians don’t usually come to mind when thinking about apex predators. But in prehistoric swamps, they absolutely could be.

Prionosuchus — The Permian River Leviathan

Long before crocodiles and spinosaurids claimed riverbanks, South America’s Permian waterways were ruled by Prionosuchus. This enormous amphibian may have reached lengths of 30 feet, making it one of the largest temnospondyls ever discovered.

Its skull was long and narrow, packed with interlocking teeth suited for gripping fish and other aquatic animals. Structurally, it resembled a giant gharial, optimized for snapping sideways through water with minimal resistance. That streamlined snout suggests a life spent almost entirely in rivers and swamps.

Prionosuchus likely lay partially submerged, its eyes positioned high on the skull to scan above the surface. In shallow, vegetation-choked waterways, visibility would have been poor. That favored ambush over pursuit. A sudden lateral strike, a powerful clamp of the jaws, and prey would be dragged under.

In the Permian world, before dinosaurs even existed, rivers already had monsters waiting beneath the surface.

Metoposaurus — The Seasonal Swamp Hunter

Another temnospondyl amphibian, Metoposaurus, thrived during the Late Triassic. Unlike Prionosuchus, Metoposaurus had a broad, flat skull with eyes positioned toward the top, giving it a distinctly crocodile-like appearance.

It lived in floodplains and seasonal swamps that dried out periodically. Fossil beds show mass accumulations, suggesting these animals congregated in shrinking water sources during droughts.

In such environments, hunting becomes opportunistic. Fish trapped in shallow pools, small reptiles searching for water, even other amphibians — all would have been potential prey.

Metoposaurus likely relied on sudden upward lunges from muddy bottoms, snapping at anything that moved within range. Its wide jaw opening allowed it to engulf prey quickly rather than tear it apart.

Swamps aren’t stable ecosystems. Water levels rise and fall. Vegetation shifts. But predators like Metoposaurus adapted to that instability, turning seasonal chaos into opportunity.

Suchomimus — The River Edge Specialist

Closely related to Baryonyx, Suchomimus inhabited river systems in what is now Africa during the Early Cretaceous.

Its name means “crocodile mimic,” and the skull shows why. Long, narrow jaws and conical teeth were perfectly suited for catching fish. But Suchomimus wasn’t fully aquatic. Its long legs suggest it spent considerable time walking along riverbanks, scanning for movement in shallow water.

This dual lifestyle created a versatile hunter. It could wade into rivers, strike at fish, then retreat onto land to avoid larger aquatic predators.

In complex wetland systems, flexibility often determines survival. Suchomimus wasn’t as massive as Spinosaurus, but it likely filled an important niche — a mid-to-large predator exploiting both land and water edges.

The margins of rivers are where ecosystems overlap. And predators that understand both environments hold a powerful advantage.

Why Rivers and Swamps Breed Apex Hunters

Wetlands concentrate life.

Fish gather in channels. Herbivores approach to drink. Smaller animals seek cover among reeds and roots. Seasonal flooding deposits nutrients, creating dense food webs.

That density attracts predators.

Unlike open plains, rivers and swamps limit visibility and movement. Water slows escape. Mud traps the unwary. Vegetation hides both hunter and prey.

Ambush becomes the dominant strategy. Speed matters less than positioning. Power matters less than timing.

From Permian amphibians like Prionosuchus to Cretaceous crocodilians like Deinosuchus, prehistoric wetlands consistently produced large, patient hunters designed for sudden violence.

The pattern repeats across millions of years because the environment demands it.

Shallow water favors concealment.

Dense vegetation favors surprise.

Soft ground favors creatures adapted to both land and water.

Even today, some of the most dangerous predators — crocodiles, anacondas, large catfish — dominate similar habitats. The blueprint hasn’t changed much.

Ancient rivers were not peaceful places. Beneath still water, in shadowed channels and reed-choked banks, evolution repeatedly shaped predators that mastered patience.

And in wetlands, patience is lethal.