Long before jet streams carried modern aircraft and before eagles traced circles above mountain ridges, the sky was already a contested domain. It wasn’t empty blue space — it was territory. A three-dimensional battlefield where survival demanded engineering precision, extreme adaptation, and relentless refinement.

Flight is one of evolution’s most difficult achievements. To leave the ground, an animal must solve a series of biological problems at once: reduce weight without sacrificing strength, develop muscles powerful enough to generate lift, create surfaces capable of controlling airflow, and maintain balance while moving through unpredictable wind currents. It’s a delicate equation. And yet, over hundreds of millions of years, nature solved it multiple times.

Insects were the first to rise. Then reptiles experimented with membrane wings long before birds existed. Later, feathered dinosaurs refined flight into something more maneuverable and energy-efficient. After the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs, giant birds took their turn dominating thermals and coastlines.

Each wave of aerial rulers reflected the conditions of its era — oxygen levels, climate patterns, continental layouts, and available prey. In the Carboniferous, oxygen-rich air allowed insects to grow to astonishing sizes. In the Cretaceous, warm global climates supported pterosaurs with wingspans rivaling small aircraft. During the Miocene and Pleistocene, enormous birds glided over open plains and ocean currents with quiet authority.

To rule the sky is not simply to fly. It is to control vantage, to dictate perspective. From above, prey becomes visible long before it senses danger. Migration becomes efficient. Escape becomes multidirectional. The sky offers reach, surveillance, and strategic superiority.

And in prehistoric times, that advantage belonged to giants.

Some were reptiles with wings made of stretched skin and elongated fingers.

Some were birds with vast feathered spans riding warm air currents.

Some were insects that filled the air long before vertebrates ever attempted lift.

Together, they transformed the sky into one of the most dynamic ecosystems in Earth’s history — a realm where gravity was challenged, and dominance was measured in wingspan.

Pteranodon — The Coastal Soarer

Few prehistoric flyers are as iconic as Pteranodon.

With a wingspan reaching up to 7 meters (over 20 feet), Pteranodon was built for gliding over vast coastal waters. Unlike birds, it had no feathers. Its wings were formed from a membrane of skin and muscle stretching from an elongated fourth finger to its body.

Its long, toothless beak suggests a diet focused largely on fish. Much like modern seabirds, it likely skimmed above ocean surfaces and dove down to snatch prey. Fossil evidence places it in marine environments, indicating strong ties to coastal ecosystems.

What made Pteranodon a sky ruler wasn’t brute aggression. It was efficiency. Large wings allowed it to ride thermals and ocean winds for long periods with minimal energy expenditure. In prehistoric shorelines filled with marine life, that advantage meant access to abundant food.

Above the Cretaceous seas, Pteranodon would have been a constant presence — gliding silhouettes against the horizon.

Quetzalcoatlus — The Giant of the Air

If Pteranodon was impressive, Quetzalcoatlus redefined scale.

This azhdarchid pterosaur may have had a wingspan approaching 10–11 meters (around 35 feet). That rivals the wingspan of a small airplane.

Quetzalcoatlus was not built like a typical seabird. Its long neck, elongated legs, and narrow jaws suggest a different lifestyle. Many paleontologists believe it hunted on land, stalking small animals across floodplains and river systems before launching back into the air.

The mechanics of its takeoff are fascinating. Rather than running like birds, it likely used a quadrupedal launch — pushing off with both wings and legs in a powerful vault. That method would have allowed even such a massive animal to achieve lift efficiently.

To stand beneath Quetzalcoatlus would have been unsettling. Its height on the ground may have rivaled a giraffe’s shoulder. And yet it could lift into the sky.

That combination of terrestrial dominance and aerial command makes it one of the most extraordinary flying animals in Earth’s history.

Hatzegopteryx — The Apex Aerial Predator

Closely related to Quetzalcoatlus, Hatzegopteryx may have been even more intimidating.

Fossils suggest it had a shorter, more robust neck and an exceptionally strong skull compared to other azhdarchids. This hints at a more aggressive hunting style.

Hatzegopteryx lived on what was once an island ecosystem in Europe. In such environments, predators often evolve unique behaviors. It may have been one of the top predators in its habitat, capable of seizing relatively large prey.

Unlike seabird-like pterosaurs, this species likely stalked terrestrial animals, using its long beak to grab and dispatch prey swiftly.

To be hunted from above is one thing. To be hunted by something that can land, walk, and then rise into the air again is another.

Argentavis — The Giant Bird of Prehistoric South America

After the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs, birds began exploring larger body sizes. One of the most spectacular examples is Argentavis magnificens.

Living during the Miocene epoch, Argentavis had a wingspan of around 6–7 meters. Unlike pterosaurs, it was a true bird with feathers and a powerful beak.

Argentavis likely relied heavily on soaring flight. It may have used thermal updrafts over open plains, conserving energy while scanning for carcasses or small prey.

Some researchers believe it behaved similarly to modern condors, possibly scavenging large mammals. Others suggest it may have actively hunted smaller animals.

Either way, its presence in the sky would have been dominant. With that wingspan, few other flying animals could compete directly.

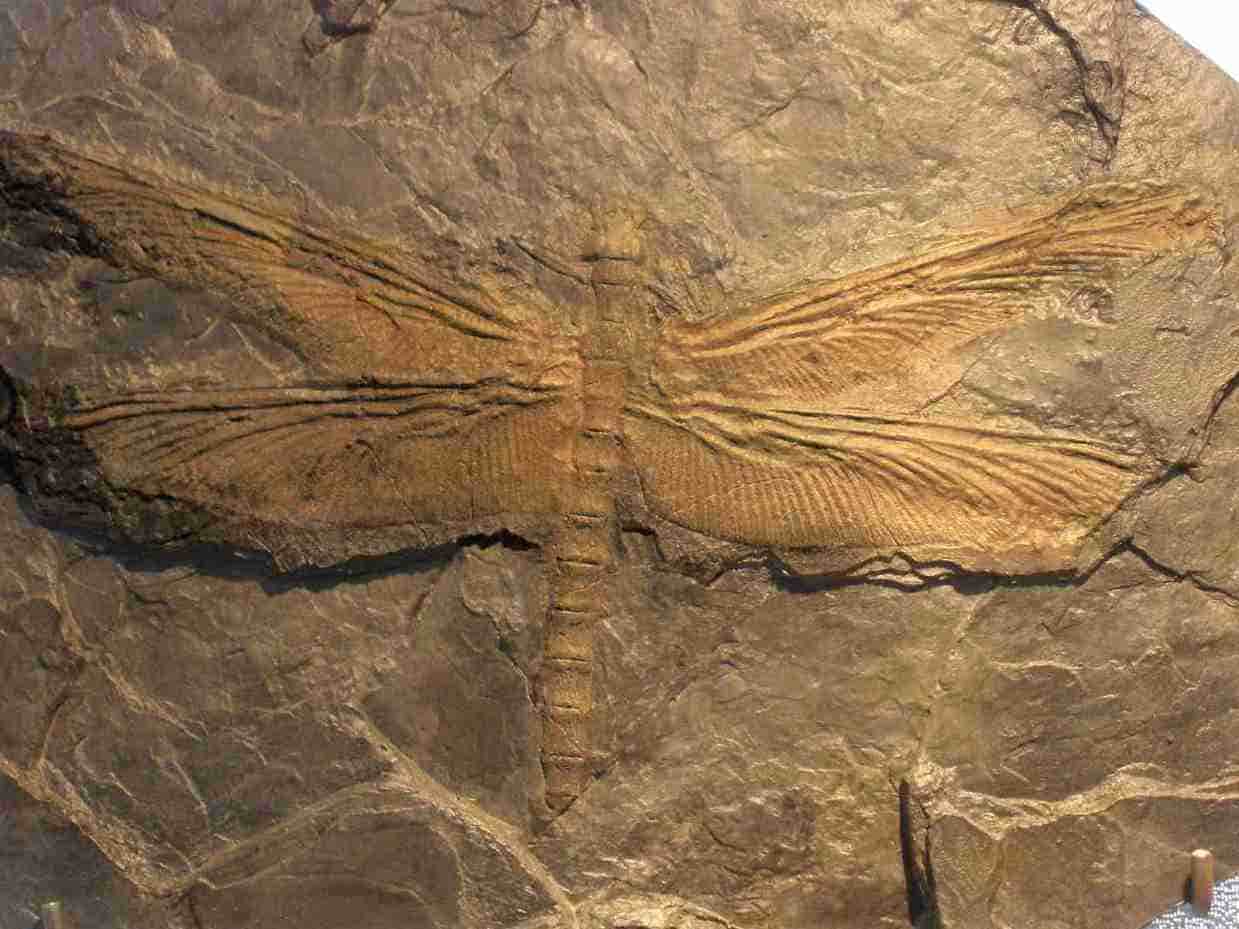

Meganeura — The Insect That Owned the Carboniferous Sky

Long before reptiles and birds took to the air, insects ruled it.

During the Carboniferous period, oxygen levels were significantly higher than today. This allowed arthropods to grow to extraordinary sizes. Among them was Meganeura, a dragonfly-like insect with a wingspan of up to 70 centimeters.

That may not sound enormous compared to pterosaurs, but in a world without birds or bats, Meganeura had little aerial competition.

With large compound eyes and agile flight, it was likely an efficient predator, capturing smaller insects mid-air.

To early terrestrial animals, the sky itself was controlled by giant insects.

It’s easy to overlook Meganeura because it’s small compared to later giants. But in its time, it was the apex aerial hunter.

Pelagornis — The Oceanic Glider

Millions of years after the last pterosaurs vanished, another giant mastered open skies above the sea: Pelagornis.

Pelagornis belonged to a group of “bony-toothed” birds. Its beak wasn’t lined with true teeth, but with sharp, tooth-like projections of bone. These structures likely helped it grip slippery fish pulled from the ocean surface.

With a wingspan estimated at 6 to possibly 7 meters, Pelagornis was built for dynamic soaring — a flight style that uses wind gradients above waves to travel long distances with minimal effort. Modern albatrosses do something similar, but Pelagornis may have done it on a grander scale.

It didn’t need speed like a falcon. It needed endurance. Endless coastline, open sea winds, and patience.

Over Miocene oceans, Pelagornis would have appeared almost mechanical in its precision — gliding low, banking with wind currents, dipping toward schools of fish.

In aerial dominance, stamina is often more powerful than aggression.

Teratornis — The North American Sky Hunter

In Ice Age North America, another giant bird ruled the thermals: Teratornis.

Teratornis was slightly smaller than Argentavis but still enormous compared to modern birds of prey. Its wingspan reached around 3.5 to 4 meters. Fossils found in tar pits suggest it lived alongside saber-toothed cats, dire wolves, and mammoths.

Unlike pure scavengers, Teratornis may have been more versatile. Its strong legs and curved beak suggest it could hunt small mammals and also feed on carrion.

Ice Age landscapes were open and wind-swept — perfect for soaring flight. From above, Teratornis would have had a wide visual field, able to detect movement across grasslands and valleys.

In cold prehistoric skies filled with mammalian megafauna, Teratornis held its place as one of the dominant aerial predators.

Archaeopteryx — The First Steps Into the Sky

Before giant pterosaurs and massive birds claimed the heavens, there was a transitional figure: Archaeopteryx.

Often described as one of the earliest known birds, Archaeopteryx lived during the Late Jurassic period. It had feathers and wings, but also teeth, clawed fingers, and a long bony tail.

Its flight ability is still debated. Some scientists argue it was capable of powered flight; others believe it mostly glided between trees. Regardless, it represents one of the first successful experiments in vertebrate flight.

In a world already inhabited by pterosaurs, Archaeopteryx didn’t dominate the sky. But it marked a turning point.

From that small, feathered form would eventually arise eagles, condors, falcons — and even the giants like Argentavis.

Sky domination doesn’t begin with giants. It begins with innovation.

Why the Sky Was Worth Conquering

Flight is expensive. It requires light bones, enormous muscle energy, and constant adaptation to weather conditions. So why did prehistoric animals repeatedly evolve it?

Because the sky offers advantages few other environments can match.

From above, prey becomes visible across vast distances.

Escape becomes possible in three dimensions.

Competition decreases when fewer animals share the same space.

In prehistoric ecosystems, the air acted as both hunting ground and refuge. Large pterosaurs could patrol shorelines with little interference. Giant birds could travel between feeding areas without crossing dangerous terrain. Even giant insects exploited aerial freedom long before vertebrates attempted it.

Each era produced its own sky rulers, shaped by climate, oxygen levels, continental arrangements, and prey availability.

What’s remarkable is how often evolution returned to the same solution: wings.

Membrane wings in pterosaurs.

Feathered wings in birds.

Veined wings in insects.

Different structures, same objective.

To rise above competitors — literally.

The End of the Prehistoric Sky Giants

The extinction event 66 million years ago ended the age of pterosaurs. Later climate shifts and ecological changes eliminated giant birds like Argentavis and Pelagornis. Oxygen levels dropped from Carboniferous highs, shrinking insect sizes dramatically.

The sky didn’t become empty — it simply changed occupants.

Today’s eagles, vultures, albatrosses, and bats are descendants of that long evolutionary history. They may not reach the scale of Quetzalcoatlus or Argentavis, but they inherit the same principle: altitude equals advantage.

When we look up at a bird circling high above, it’s easy to forget that the sky was once ruled by creatures taller than giraffes and wider than small aircraft.

Prehistoric airspace wasn’t quiet.

It was claimed.

And for millions of years, it belonged to giants.