Nature does not wake up with intention, yet it has shaped human history more violently than any empire or war. Civilizations have risen along rivers and fault lines, on fertile volcanic soil and warm coastal plains — often in places that later revealed their instability. What makes natural phenomena so deadly is not just their raw power, but the way they intersect with human settlement, infrastructure, and biology.

Some forces strike in seconds. The ground fractures. Buildings collapse. Entire cities fall silent beneath dust. Others unfold slowly and invisibly — crops fail, temperatures rise beyond tolerance, microscopic pathogens spread from village to continent. In certain cases, the deadliest phase arrives after the initial event: disease after floods, famine after drought, fire after earthquakes.

The scale of these phenomena is difficult to comprehend. A tsunami can carry the energy of multiple nuclear explosions. A major volcanic eruption can alter global climate for years. A powerful cyclone can displace millions overnight. Even heat — something as ordinary as air temperature — can quietly claim tens of thousands of lives in a single summer.

What makes them especially lethal is unpredictability. Despite satellites, seismic monitoring systems, and advanced forecasting, many natural disasters still strike with limited warning. And even when warnings exist, evacuation, preparedness, and infrastructure determine survival.

Throughout recorded history, natural phenomena have caused death tolls that rival the most devastating conflicts. Some erased entire towns. Others reshaped political borders. A few changed the course of human development entirely.

Understanding these forces is not simply about fear. It is about recognizing the boundaries of human control — and the consequences when those boundaries are crossed.

Earthquakes – Cities Lost in Seconds

Earthquakes remain among the most lethal natural disasters because of their suddenness and the structural collapse they trigger. When tectonic plates release accumulated stress along fault lines, the energy travels outward as seismic waves. The ground shifts violently — sometimes for less than a minute — but that minute can be fatal.

One of the deadliest earthquakes ever recorded struck Shaanxi Province, China, in 1556. Estimated deaths reached approximately 830,000 people. Many lived in cave dwellings carved into loess soil cliffs, which collapsed during the tremors.

In 1976, the Tangshan earthquake in China killed an estimated 242,000 people, though some unofficial estimates place the number even higher. The quake struck a densely populated industrial city at 3:42 AM, when most residents were asleep. Buildings crumbled within seconds.

The 2010 Haiti earthquake, measuring magnitude 7.0, killed over 200,000 people. The devastation was amplified by poor construction standards and high population density in Port-au-Prince. Infrastructure collapsed almost instantly.

Even powerful quakes in developed regions can cause massive destruction. The 1906 San Francisco earthquake triggered fires that burned for days, destroying much of the city.

The danger of earthquakes lies in three factors: unpredictability, structural vulnerability, and cascading effects such as fires, landslides, and tsunamis.

Tsunamis – When the Ocean Turns Violent

Tsunamis are typically triggered by undersea earthquakes that vertically displace the seafloor. When this happens, vast quantities of water are pushed upward, generating waves that travel across oceans at jetliner speeds.

The deadliest modern example remains the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Triggered by a magnitude 9.1 earthquake off the coast of Sumatra, Indonesia, the tsunami killed over 230,000 people across 14 countries. Entire coastal communities were erased within minutes.

The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan killed nearly 20,000 people and triggered the Fukushima nuclear disaster. The tsunami waves exceeded 40 meters in some areas.

Tsunamis are particularly lethal because they often arrive in multiple waves. The first surge may not be the largest. Survivors returning to flooded zones sometimes face even larger subsequent waves.

Water carries immense force. It sweeps away vehicles, buildings, and human bodies alike. And unlike storms, tsunamis can strike coastlines far from the original earthquake epicenter.

Volcanic Eruptions – Pyroclastic Death

Volcanic eruptions vary widely in scale, but the largest have shaped global climate and caused mass death.

The 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia is considered the most powerful in recorded history. It killed approximately 71,000 people, both directly and indirectly. Ash blocked sunlight, leading to the “Year Without a Summer” in 1816. Crop failures and famine spread across continents.

In 79 AD, Mount Vesuvius buried Pompeii and Herculaneum. While estimated deaths range from several thousand to over 15,000, many victims died from pyroclastic surges — superheated gas clouds exceeding 500°C that suffocated and incinerated inhabitants within moments.

The 1902 eruption of Mount Pelée on Martinique killed around 30,000 people in minutes when a pyroclastic flow destroyed the city of Saint-Pierre.

Volcanic deaths often result from secondary effects: ash inhalation, roof collapse, contaminated water, and long-term agricultural failure.

Volcanoes combine explosive force with atmospheric consequences.

Tropical Cyclones – Storms That Drown Nations

Hurricanes, typhoons, and cyclones differ in name but share structure: rotating systems fueled by warm ocean water.

The deadliest tropical cyclone on record occurred in 1970 — the Bhola cyclone in what is now Bangladesh. It killed an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 people. Low-lying coastal geography amplified the storm surge, which inundated villages overnight.

In 2008, Cyclone Nargis struck Myanmar, killing more than 138,000 people. The devastation was compounded by limited early warning systems and slow disaster response.

Storm surge remains the leading cause of death in tropical cyclones. As ocean water rises and moves inland, it floods homes rapidly, often at night.

Unlike earthquakes, cyclones provide days of satellite tracking. Yet evacuation is not always possible in densely populated or impoverished regions.

Heatwaves – Death Without Spectacle

Heatwaves do not flatten buildings, but they quietly increase mortality on a massive scale.

In 2003, a European heatwave killed an estimated 70,000 people across multiple countries. Temperatures remained abnormally high for weeks. Elderly individuals living alone were particularly vulnerable.

In 2010, a Russian heatwave caused approximately 55,000 excess deaths and triggered widespread wildfires.

Heat kills by overwhelming the body’s cooling system. When core temperature rises beyond 40°C (104°F), organs begin to fail. Without rapid cooling, death can occur.

Because heatwaves often strike urban areas with heat-retaining concrete and limited airflow, they are sometimes deadlier in cities than in rural areas.

Drought and Famine – Slow Catastrophe

Unlike sudden disasters, drought unfolds gradually. Crops fail. Livestock die. Water sources dry up.

The Ethiopian famine of 1983–1985, triggered in part by drought, resulted in hundreds of thousands of deaths. In broader history, prolonged droughts have contributed to the collapse of civilizations.

Drought rarely kills directly through dehydration alone. Instead, it leads to food shortages, malnutrition, disease outbreaks, and political instability.

It is deadly because it lingers.

Floods – Water as a Force of Erasure

Floods are among the most underestimated natural killers in human history. Unlike earthquakes or volcanoes, they do not always appear dramatic. Water rises, spreads, and consumes quietly — but the scale can be enormous.

The deadliest flood ever recorded occurred in 1931 in China along the Yangtze and Huai Rivers. Following months of heavy rain and snowmelt, massive flooding devastated entire provinces. Estimates of deaths range from 1 million to as high as 4 million people when accounting for famine and disease that followed.

In 1887, another Yellow River flood killed approximately 900,000 people. Entire villages were swallowed as levees failed.

Floods kill in multiple ways: drowning during the initial surge, disease outbreaks afterward, and long-term displacement. Water contaminates drinking supplies, spreads pathogens, and destroys crops.

What makes floods especially lethal is their recurrence. Many occur in low-lying river basins where populations have lived for centuries because of fertile soil. That same fertility comes with risk.

Landslides – Mountains in Motion

Landslides often accompany earthquakes and heavy rainfall, but they can also occur independently. When slopes become unstable, gravity does the rest.

One of the deadliest landslide-related disasters happened in 1985 after the eruption of Nevado del Ruiz in Colombia. The eruption melted glacial ice, generating lahars — volcanic mudflows — that buried the town of Armero. Around 23,000 people died.

In 1970, a massive rock and ice avalanche in Peru’s Andes was triggered by an earthquake. The avalanche engulfed the town of Yungay, killing approximately 20,000 people in minutes.

Landslides are terrifying because they move fast and carry enormous weight. Entire hillsides collapse, burying structures under meters of debris.

Often, the warning signs are subtle: cracked soil, small rockfalls, heavy rain. Then the slope gives way.

Lightning – Instant and Indiscriminate

Lightning is responsible for thousands of deaths globally each year. While individual strikes may seem random, certain regions experience extraordinary frequency.

Lake Maracaibo in Venezuela is known for nearly constant lightning storms during parts of the year — sometimes producing thousands of strikes per night.

A lightning bolt can heat surrounding air to temperatures hotter than the surface of the sun. The electrical current passing through a human body can cause cardiac arrest, severe burns, neurological damage, and instant death.

Unlike hurricanes or floods, lightning deaths often occur during everyday activities — farming, hiking, fishing.

Its lethality lies in speed. There is no negotiation with a lightning strike.

Avalanches – Snow as a Weapon

In mountainous regions, snow can accumulate in unstable layers. A small trigger — a sound, vibration, or even a skier’s movement — can release thousands of tons of snow down a slope.

In 1970, the same Peruvian earthquake that triggered landslides also caused avalanches in the Andes, compounding devastation.

On Mount Everest and other Himalayan peaks, avalanches have killed climbers and support staff repeatedly. In 2014, an avalanche on Everest killed 16 Sherpa guides. In 2015, another avalanche triggered by a massive earthquake killed 22 people at base camp.

Avalanches kill by burial and suffocation. Victims trapped under snow have limited oxygen and minutes to survive unless rescued.

Snow appears soft and silent. In motion, it becomes crushing.

Wildfires – Infernos Fueled by Climate

Wildfires are natural components of many ecosystems, but under certain conditions they become catastrophic.

The 2019–2020 Australian bushfires burned millions of hectares, destroyed thousands of homes, and caused dozens of direct deaths. Indirectly, smoke inhalation is believed to have contributed to hundreds more.

In 2018, the Camp Fire in California killed 85 people, becoming the deadliest wildfire in modern U.S. history.

Wildfires kill through burns, smoke inhalation, and rapid spread. Strong winds can push flames faster than vehicles can outrun them.

Climate change, prolonged drought, and expanding human settlements into fire-prone regions have increased wildfire intensity and impact.

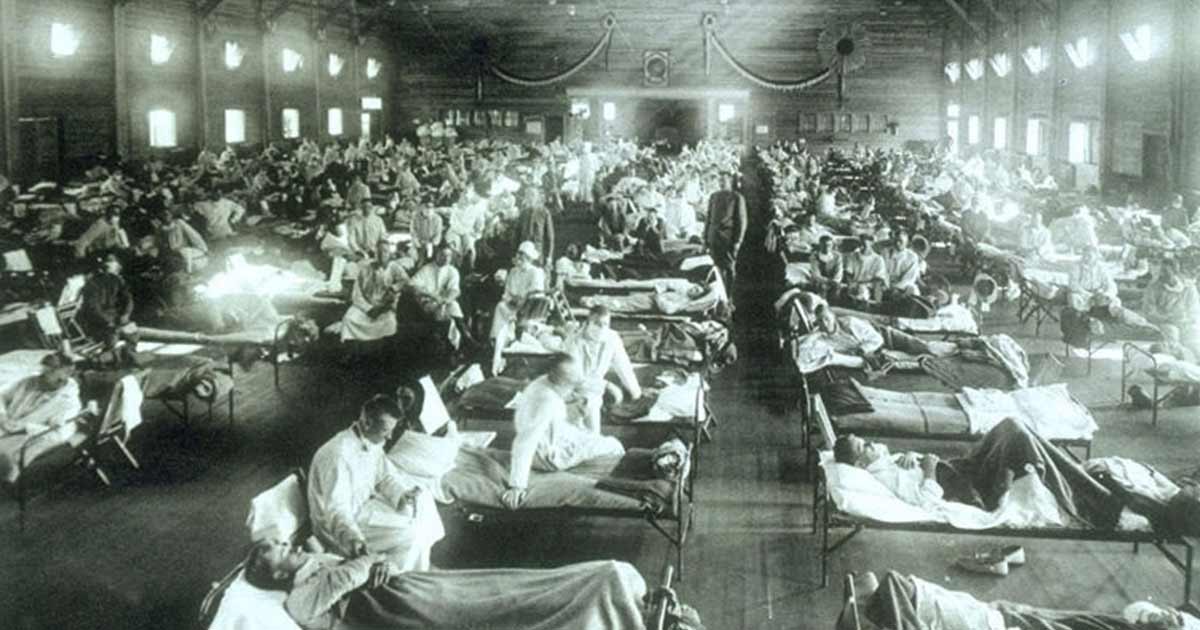

Pandemics – Biological Natural Disasters

Though often associated with human society, pandemics originate in natural biological processes. Viruses and bacteria evolve, mutate, and jump between species.

The Black Death in the 14th century killed an estimated 75 to 200 million people across Europe, Asia, and North Africa. It remains one of the deadliest events in human history.

In 1918, the influenza pandemic killed approximately 50 million people worldwide.

Pandemics differ from geological disasters in timescale. They spread over months or years. Yet their lethality can surpass that of earthquakes and floods combined.

Unlike storms or eruptions, pandemics are invisible. Transmission occurs silently.

Extreme Cold Waves – Freezing as a Killer

Cold waves can drop temperatures far below seasonal norms. In 1936, a North American cold wave caused hundreds of deaths, freezing rivers and infrastructure.

Hypothermia occurs when body temperature falls below 35°C (95°F). Organs slow. Heart rhythm becomes unstable. Confusion sets in.

Extreme cold does not require wilderness. Urban cold snaps can be lethal for homeless populations and those without heating.

Like heatwaves, cold waves kill without spectacle.

Across continents and climates, the deadliest natural phenomena share a common trait: they expose human vulnerability.

Earthquakes shatter foundations. Floods erase boundaries. Heat and cold overwhelm physiology. Storms uproot entire coastlines. Disease spreads invisibly.

Nature does not escalate to prove a point. It follows physical laws. But when those laws converge with human density, the outcome can be catastrophic.