When people imagine deserts, they usually picture endless sand dunes glowing under a relentless sun. But deserts are far more complex than that. Some are rocky plateaus. Some are frozen wastelands. Some are salt-crusted plains that look like alien landscapes. What unites them is not sand — it is scarcity. Scarcity of water, shade, predictable weather, and sometimes even oxygen.

Deserts become deadly not because they are dramatic, but because they are indifferent. They do not need to attack. They simply remove what humans depend on: hydration, shelter, stability. A wrong turn, a broken vehicle, a misjudged distance — that is often all it takes.

Across the planet, certain deserts have earned reputations not just for harshness, but for lethality.

The Sahara Desert – Vast and Unforgiving

The Sahara is the largest hot desert in the world, stretching across North Africa and covering an area roughly the size of the United States. Its sheer scale is part of what makes it deadly.

Temperatures during the day can exceed 50°C (122°F), while nights may drop close to freezing. Dehydration becomes life-threatening within hours without adequate water. The human body loses fluid rapidly through sweat, and without replacement, blood thickens, organs strain, and confusion sets in.

But heat is only one threat.

Sandstorms can reduce visibility to near zero, disorienting travelers and burying equipment. In remote regions, help may be hundreds of kilometers away. Historically, entire caravans vanished when navigation failed.

The Sahara is not uniformly sand. Large portions consist of rocky plains and gravel fields where shade is nonexistent. Water sources are rare and often seasonal.

Its danger lies in scale. There is simply too much emptiness.

The Atacama Desert – The Driest Place on Earth

Located in northern Chile, the Atacama Desert is often described as the driest non-polar desert on Earth. Some weather stations there have recorded years without measurable rainfall.

The landscape looks otherworldly — salt flats, volcanic peaks, and mineral-rich soil that resembles Mars. In fact, space agencies test Mars rovers there because of its extreme dryness.

The danger of the Atacama is dehydration compounded by altitude. Parts of the desert lie at high elevation, where oxygen levels drop and altitude sickness becomes a real risk.

Without water, survival time is short. And unlike tropical environments where vegetation signals moisture, the Atacama offers almost no visual clues. The ground itself holds virtually no usable water.

For travelers, miscalculating supplies can quickly turn exploration into emergency.

The Arabian Desert – Heat and Sandstorms

Spanning much of the Arabian Peninsula, this desert includes the Rub’ al Khali — the Empty Quarter — one of the largest continuous sand deserts in the world.

Temperatures can reach extreme highs, and sandstorms known as “haboobs” can arise with little warning. These storms are powerful enough to halt transportation and disorient experienced desert navigators.

The dunes shift constantly. Landmarks disappear. What looks like a nearby ridge may take hours to reach.

Historically, travelers relied on stars, wind patterns, and tribal knowledge to navigate safely. Even today, vehicles can become trapped in soft sand, and recovery may require specialized equipment.

The danger here is not just heat, but disorientation.

The Gobi Desert – Extreme Temperature Swings

The Gobi Desert, stretching across Mongolia and northern China, defies the stereotype of a scorching sand sea. Much of it is rocky terrain rather than dunes.

What makes the Gobi deadly is its temperature volatility.

Summer temperatures can soar above 40°C (104°F), while winter temperatures plunge below -40°C (-40°F). Such dramatic swings place immense stress on the human body. Exposure can lead to heatstroke in one season and frostbite in another.

Strong winds and sudden dust storms further complicate survival. In remote areas, infrastructure is minimal, and distances between settlements are vast.

The Gobi teaches a different lesson: deserts are not always about heat. They are about extremes.

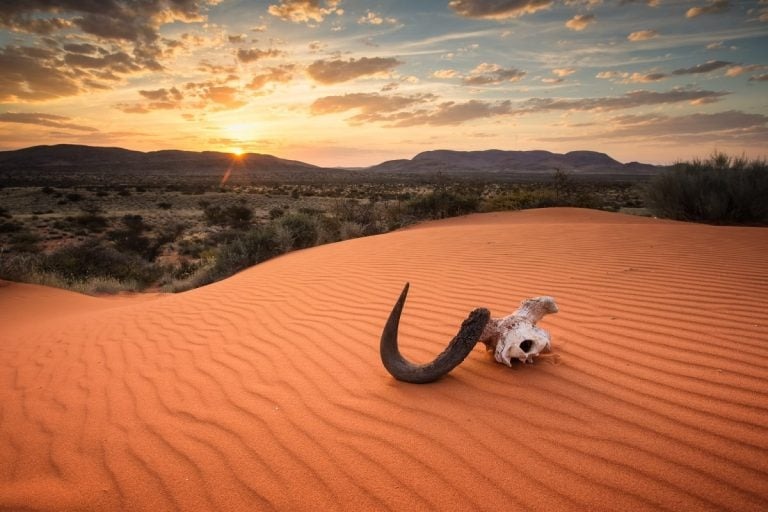

The Kalahari Desert – Hidden Dangers

The Kalahari in southern Africa appears less hostile at first glance. It supports wildlife and sparse vegetation. But its dangers are subtle.

Water sources can vanish seasonally. Travelers may assume that vegetation means hydration is available, but many plants there do not provide drinkable water.

Wildlife presents another layer of risk. Lions, hyenas, venomous snakes, and scorpions inhabit the region. While animal attacks are rare compared to dehydration risks, they remain a factor.

The San people have lived in the Kalahari for thousands of years, surviving through deep knowledge of the land — knowing which roots contain moisture and how to track seasonal changes.

Without that knowledge, survival becomes uncertain.

Death Valley – Heat Records and Human Error

Despite its ominous name, Death Valley in California is a national park and tourist destination. Yet it holds the record for some of the highest air temperatures ever recorded on Earth.

Summer temperatures regularly exceed 49°C (120°F). Vehicle breakdowns are common in extreme heat. Hikers who underestimate conditions can suffer heat exhaustion or heatstroke rapidly.

Unlike more remote deserts, Death Valley’s danger often comes from overconfidence. Because roads and facilities exist, visitors may assume safety is guaranteed.

But in extreme heat, even short walks can become deadly without sufficient water.

The Danakil Depression – A Furnace Below Sea Level

In northeastern Ethiopia lies one of the most hostile landscapes on Earth. The Danakil Depression sits below sea level and ranks among the hottest inhabited places in the world. Average temperatures often exceed 34°C (93°F) year-round, and peak daytime temperatures climb far higher.

But heat alone does not define this desert.

The region is geologically unstable. Active volcanoes, lava lakes, and hydrothermal fields shape the terrain. Sulfur springs bubble in neon shades of yellow and green. Toxic gases seep from fissures in the ground. Acidic pools can burn skin. The air smells of sulfur and minerals.

Walking here feels like stepping onto another planet — and in some areas, that impression is accurate. Scientists study the Danakil because its chemistry resembles early Earth conditions and even certain Martian environments.

For humans, though, it is brutally dangerous. Heatstroke, dehydration, toxic fumes, and unstable ground combine in a landscape that does not forgive mistakes. Local Afar communities navigate the terrain with experience and caution, but for outsiders, the environment can quickly become overwhelming.

The Simpson Desert – Remote and Relentless

Australia’s Simpson Desert is defined by parallel sand dunes stretching hundreds of kilometers. The red sand ridges look uniform, almost hypnotic.

Its danger lies in remoteness.

Roads are minimal. Communication signals are unreliable. If a vehicle breaks down deep within the dunes, rescue may take days. Water sources are scarce and unpredictable. Summer temperatures rise above 45°C (113°F), and shade is limited.

The desert also hosts venomous snakes and spiders, but dehydration remains the primary threat.

Navigation across the dunes requires skill. Without GPS or detailed knowledge, the repetitive landscape can cause disorientation. What appears to be forward progress may simply be circling between ridges.

The Simpson is not famous globally like the Sahara, but it has claimed lives through isolation and underestimation.

The Namib Desert – Where Desert Meets Ocean

The Namib Desert in southwestern Africa is one of the oldest deserts on Earth. Its towering dunes near the coast are iconic — massive waves of sand rising beside the Atlantic Ocean.

Paradoxically, fog from the cold Benguela Current drifts inland, creating surreal scenes where dunes meet mist. That fog sustains certain plants and insects, but it does little for stranded humans.

The combination of desert heat and cold ocean currents makes survival complex. Fresh water is rare. Coastal shipwrecks dot parts of the Skeleton Coast, where sailors once reached land only to die of thirst.

The ocean offers no easy rescue. Strong currents and rough surf make swimming dangerous. The land behind provides little shelter.

The Namib is beautiful, but it traps those who misjudge it.

The Mojave Desert – Subtle but Lethal

The Mojave Desert spans parts of California, Nevada, Arizona, and Utah. It includes Death Valley but extends far beyond it.

Unlike more remote deserts, the Mojave lies near major cities. Highways cross it. Tourists pass through regularly.

That accessibility hides risk.

Summer heat is intense. Flash floods can occur during sudden storms, transforming dry washes into raging channels. Rattlesnakes and scorpions inhabit the terrain. In some areas, abandoned mines create physical hazards.

Because people often underestimate the Mojave, thinking of it as “just another dry area,” preparation can be insufficient. Running out of water even a short distance from a vehicle can quickly escalate into a medical emergency.

The Mojave proves that proximity to civilization does not eliminate danger.

The Antarctic Desert – Cold as a Killer

When people think of deserts, they imagine heat. Yet Antarctica is technically the largest desert on Earth because of its extremely low precipitation.

Here, danger comes from cold rather than heat.

Temperatures can drop below -60°C (-76°F) inland. Frostbite can occur in minutes. Wind speeds amplify cold through wind chill, stripping heat from exposed skin rapidly.

Whiteout conditions reduce visibility to near zero. Crevasses hidden beneath snow can swallow vehicles or explorers. Rescue operations are complicated by distance and weather.

Survival requires specialized equipment, training, and logistical support. Antarctica’s danger is systematic. Without preparation, the human body simply cannot withstand it.

The Karakum Desert – Gas and Isolation

Covering much of Turkmenistan, the Karakum Desert is known for vast sand plains and sparse population.

Within it lies the “Door to Hell,” a massive gas crater that has burned continuously for decades. Originally ignited during a Soviet drilling operation to prevent methane spread, the crater now glows with constant fire.

Beyond the spectacle, the desert itself is harsh. Summer temperatures soar. Water is limited. Infrastructure outside major routes is minimal.

The Karakum demonstrates another desert risk: industrial remnants left behind in fragile environments.

Across continents, deserts test the same human vulnerabilities in different ways. Some dehydrate you. Some freeze you. Some choke you with toxic gases. Some isolate you so completely that rescue becomes uncertain.

The deadliest deserts do not always look dramatic. Sometimes they appear calm, silent, and almost inviting. That silence is what makes them dangerous.