Pesticides are designed to kill. That fact often gets softened by marketing language—“crop protection,” “pest control,” “plant health.” But at their core, many pesticides work by attacking nervous systems, shutting down respiration, disrupting cell function, or poisoning organs. Insects die because of these effects. Humans die for the same reasons, just less predictably and often more slowly.

For decades, some of the most dangerous chemicals ever manufactured were sold legally as pesticides. They were sprayed on crops, stored in homes, handled by farmers, and absorbed by workers with minimal protection. Some caused immediate death. Others caused slow neurological collapse, organ failure, or cancers that appeared years later. In many cases, the danger was known but minimized, ignored, or buried under economic pressure.

This article examines chemicals used in pesticides that have killed humans, how they work, why they were so widely used, and what makes them especially dangerous outside of controlled laboratory conditions.

Why pesticide chemicals are uniquely dangerous to humans

Unlike many industrial chemicals, pesticides are designed to spread easily. They must dissolve in water or oil, cling to surfaces, penetrate biological tissue, and remain stable long enough to do their job. These same properties make them dangerous to people.

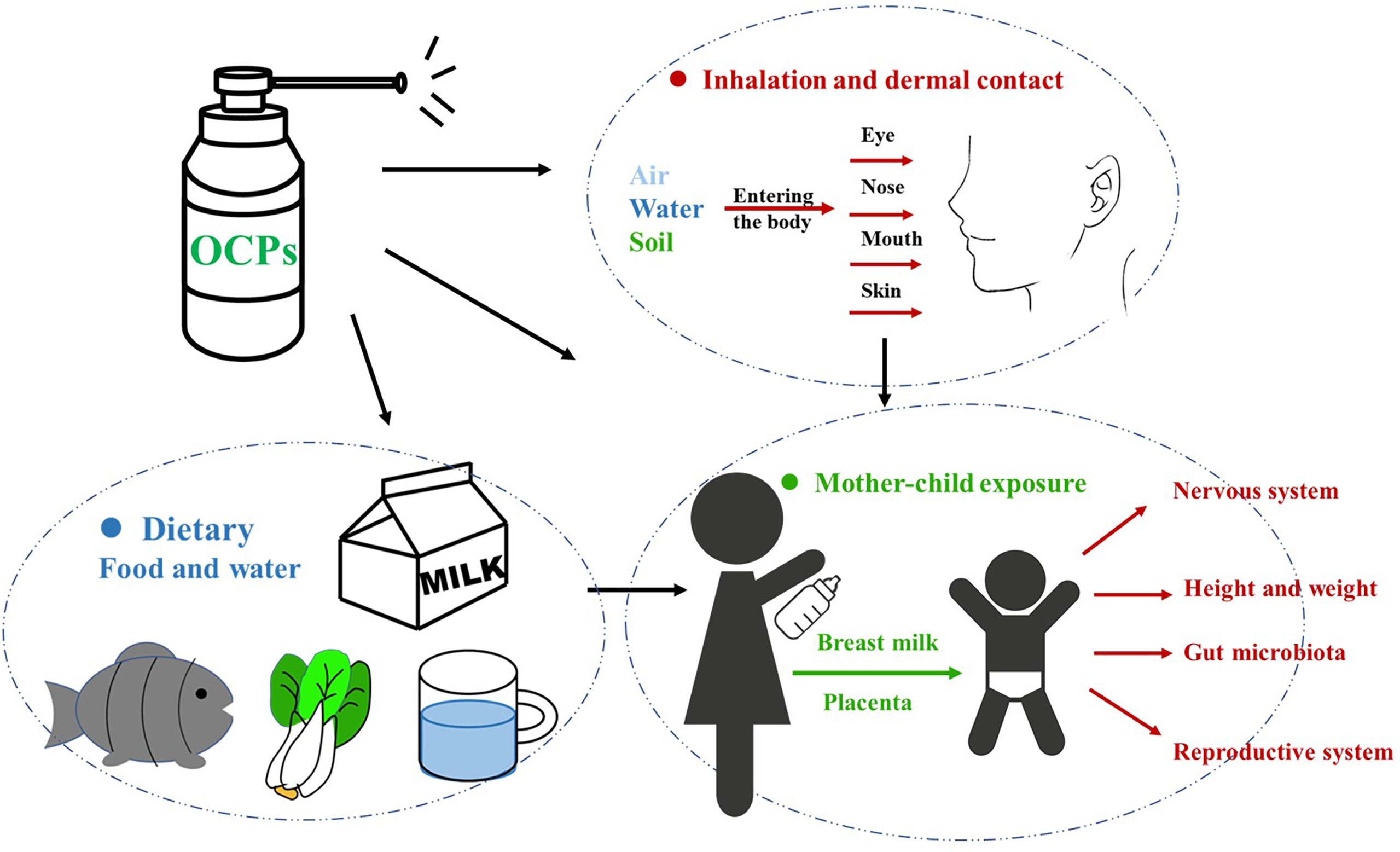

Many pesticides are neurotoxins. Others interfere with cellular respiration or hormone signaling. Some are fat-soluble, allowing them to accumulate in the body over time. Exposure does not always require swallowing. Inhalation, skin contact, or contaminated food can be enough.

Another problem is scale. Pesticides are used repeatedly, often daily, over long periods. This turns small exposures into chronic poisoning. In agricultural regions, entire populations have been exposed without realizing it.

Organophosphates and nervous system shutdown

Organophosphate pesticides are among the deadliest chemicals ever used in agriculture.

They work by inhibiting an enzyme essential for nerve function. When this enzyme is blocked, nerves fire uncontrollably. Muscles spasm, breathing becomes impossible, and the heart eventually fails.

In humans, acute organophosphate poisoning causes sweating, vomiting, seizures, respiratory paralysis, and death if untreated. Chronic exposure leads to memory loss, depression, motor dysfunction, and permanent brain damage.

These chemicals were widely used for decades on crops, in homes, and even on pets. Thousands of deaths have been recorded worldwide, especially among farm workers and in cases of accidental or intentional ingestion.

What makes organophosphates especially disturbing is their connection to chemical warfare agents. Some nerve gases were derived directly from pesticide research. The difference between a crop spray and a weapon was often only a matter of concentration.

Carbamates and fast-acting toxicity

Carbamate pesticides operate similarly to organophosphates, but with a shorter duration of action. That shorter duration was once seen as a safety advantage. In practice, carbamates have still caused widespread poisoning and death.

Symptoms appear rapidly: dizziness, nausea, muscle weakness, breathing difficulty, and collapse. High doses can kill within hours.

Carbamates were commonly used in agriculture and household pest control. Because their effects can resemble flu or heat exhaustion, poisonings were often misdiagnosed or underreported.

In regions with limited medical access, carbamate exposure has been fatal simply because treatment did not arrive in time.

Paraquat and irreversible organ failure

Paraquat is one of the most notorious pesticide chemicals ever produced.

It does not primarily attack the nervous system. Instead, it causes massive oxidative damage to cells, particularly in the lungs. Even small amounts can lead to respiratory failure days or weeks after exposure.

There is no effective antidote.

People poisoned by paraquat often survive the initial exposure, only to slowly suffocate as lung tissue scars and oxygen exchange becomes impossible. Kidney and liver failure frequently follow.

Paraquat has killed thousands of people worldwide, both accidentally and through suicide. Its toxicity is so extreme that many countries have banned it outright, yet it is still used in some regions due to its effectiveness and low cost.

Organochlorines and long-term poisoning

Organochlorine pesticides, such as DDT and related compounds, were once celebrated as miracle chemicals. They were highly effective, persistent, and cheap.

That persistence turned out to be the problem.

These chemicals accumulate in fat tissue and remain in the environment for decades. In humans, long-term exposure has been linked to cancer, endocrine disruption, immune system damage, and neurological disorders.

While organochlorines do not usually kill quickly, their contribution to long-term illness and premature death is substantial. Entire populations were exposed through food chains before the dangers became undeniable.

By the time restrictions were imposed, the damage had already spread globally.

Fumigants and invisible lethal gases

Some pesticides kill by becoming gas.

Fumigants are designed to penetrate soil, grain storage, or enclosed spaces. They are extremely toxic when inhaled. Exposure can cause sudden respiratory failure, heart arrhythmias, and death within minutes.

Because these chemicals are often colorless and odorless, victims may not realize they are being poisoned until symptoms become severe.

Fumigant-related deaths have occurred in warehouses, ships, farms, and even residential buildings when gases leaked or were misused. Poor ventilation turns these chemicals into silent killers.

Why deaths were underestimated for decades

Many pesticide-related deaths were never officially counted as such.

Symptoms were blamed on heat, infection, stress, or preexisting illness. Chronic effects were not connected to past exposure. Workers lacked access to healthcare or legal protection. In some cases, companies actively suppressed evidence of harm.

In developing regions, deaths were simply not recorded. In wealthier countries, regulatory agencies often relied on industry-funded studies that downplayed risk.

The result was a massive underestimation of how deadly these chemicals truly were.

The human cost behind “effective pest control”

Pesticides increased crop yields and reduced insect damage. That part of the story is real. What was ignored was the human cost.

Farm workers exposed daily. Children living near treated fields. Families storing chemicals at home. Emergency responders encountering spills. All paid a price.

The danger was not theoretical. It was lived, often fatally.

Banned pesticides and why they were finally removed

Many of the deadliest pesticide chemicals were not banned quickly. They were removed only after damage became impossible to deny.

In several cases, regulators acted only after thousands of poisonings, mounting medical evidence, and public pressure. Even then, bans were often partial or regional. A chemical restricted in one country could still be exported and used elsewhere, shifting the risk rather than eliminating it.

Paraquat is a clear example. Its link to fatal lung failure and irreversible organ damage was well established decades ago. Still, it remained widely used because it was cheap, effective, and profitable. In some regions, economic dependence outweighed human safety.

Organophosphates followed a similar pattern. As evidence of neurological damage and death accumulated, some compounds were banned, while others were reformulated or rebranded. The underlying mechanism of toxicity remained the same, but the products stayed on the market under different names.

This staggered approach meant that danger did not disappear. It migrated.

Pesticides that still kill today

Not all deadly pesticide chemicals belong to the past.

Many highly toxic compounds are still in use, especially in agriculture. Some are restricted to trained applicators, but enforcement is inconsistent. Protective equipment is often inadequate or ignored, particularly in hot climates where wearing full gear is physically exhausting.

Accidental poisonings continue to occur through spills, drift from sprayed fields, contaminated water, and improper storage. Children are especially vulnerable. Small body size, developing organs, and hand-to-mouth behavior increase risk dramatically.

In some regions, pesticides remain one of the most common means of suicide because they are accessible, potent, and fast-acting. This grim reality alone accounts for tens of thousands of deaths each year.

Acute poisoning versus slow death

One of the most dangerous misconceptions about pesticide toxicity is that danger is obvious and immediate.

Acute poisoning is dramatic. Symptoms appear quickly: vomiting, seizures, respiratory failure, collapse. These cases are more likely to be recognized and reported.

Chronic poisoning is quieter.

Repeated low-level exposure damages the nervous system, liver, kidneys, and endocrine system over years. People develop tremors, memory loss, mood disorders, fertility problems, and increased cancer risk. By the time death occurs, the connection to pesticide exposure is often missed entirely.

This is why official death counts underestimate the true impact. Many pesticide-related deaths are recorded under other diagnoses.

Skin contact and inhalation: the underestimated routes

Many people assume pesticide poisoning requires swallowing the chemical. That assumption has killed people.

Numerous pesticides pass easily through the skin. Others become airborne during mixing, spraying, or application. Inhalation delivers toxins directly to the bloodstream through the lungs, often faster than ingestion.

Farm workers mixing concentrates are at especially high risk. A splash on bare skin or inhaling fumes for a few minutes can be enough to cause serious injury or death, depending on the chemical.

Because these exposures may not feel immediately dangerous, people often continue working until symptoms suddenly escalate.

The illusion of “safe when used as directed”

Product labels often claim safety when instructions are followed. In real-world conditions, those instructions are difficult to meet.

Protective gear is expensive, uncomfortable, and sometimes unavailable. Literacy barriers make labels useless. Weather conditions spread chemicals beyond intended areas. Equipment leaks. Containers are reused improperly.

“Safe use” assumes ideal conditions. Real life rarely provides them.

This gap between theory and practice is one of the main reasons pesticide chemicals continue to kill humans long after their risks are understood.

What regulation improved—and what it didn’t

Modern regulation did reduce some of the worst abuses. Testing standards improved. Some compounds were banned. Training requirements were introduced.

But regulation has limits.

Testing often focuses on short-term toxicity, not lifelong exposure. Industry-funded studies still influence approval decisions. Enforcement varies wildly between countries. Global supply chains allow banned chemicals to reappear in different forms or markets.

The result is a system that reduces harm without eliminating it.

The uncomfortable reality

Pesticides were never neutral tools. They were poisons by design.

The tragedy lies not in their existence, but in how casually they were introduced into daily life. Chemicals capable of shutting down human nervous systems were treated as routine farm inputs. Their victims were often invisible, poor, or far from political power.

Understanding which pesticide chemicals kill humans is not about fear. It is about recognizing that effectiveness and safety are not the same thing.

The history of pesticide poisoning is a reminder that when a substance is designed to kill living organisms, the margin for error is always smaller than promised.