Nature can be unforgiving, but in many of history’s worst outdoor tragedies, it was not nature alone that killed — it was a human miscalculation. A wrong decision in thin air. A delayed evacuation before a storm. A shortcut on unstable ice. A single underestimated risk that turned fatal.

Mountains, oceans, forests, deserts — none of them are inherently malicious. Yet they amplify error. In controlled environments, mistakes are often survivable. In wilderness settings, the margin for error narrows sharply. A small oversight can cascade into disaster within minutes.

This article explores some of the deadliest human errors made in natural environments — not to assign blame, but to understand patterns. Because in nature, knowledge is protection. And history shows that certain mistakes repeat with tragic consistency.

Ignoring Weather Warnings

Few human errors are as deadly as underestimating weather.

Mount Everest has claimed over 300 lives, and in several high-profile disasters, climbers ignored deteriorating conditions. In 1996, a sudden storm trapped multiple expeditions near the summit. Despite forecasts suggesting worsening weather, summit pushes continued. Eight climbers died in a single day.

Weather shifts rapidly in mountainous terrain. Storm cells build unexpectedly. Temperatures drop fast. Winds intensify.

In coastal regions, similar patterns occur with hurricanes. Before Hurricane Katrina struck the U.S. Gulf Coast in 2005, evacuation orders were issued. Many residents delayed leaving, believing the storm would weaken or shift. The result was catastrophic flooding and over 1,800 deaths.

The error is often psychological: familiarity reduces perceived risk. When storms have passed harmlessly before, future warnings feel exaggerated — until they are not.

Overconfidence in Physical Ability

Many fatalities in nature stem from overestimating personal endurance.

Hikers venture into deserts without sufficient water. Swimmers underestimate ocean currents. Climbers attempt technical routes beyond their skill level.

In Death Valley, multiple deaths have occurred when visitors attempted short hikes in extreme heat without adequate hydration. Temperatures above 49°C (120°F) overwhelm even physically fit individuals quickly.

Cold environments pose similar risks. Hypothermia can set in gradually, impairing judgment before the victim recognizes danger. Skiers and mountaineers sometimes push forward despite early warning signs, believing they can “handle it.”

Nature does not adjust difficulty based on confidence.

Venturing Off Marked Trails

Marked trails exist for a reason.

National parks worldwide record fatalities from visitors leaving designated paths. In Yellowstone National Park, some tourists have walked onto thin crusts near geothermal areas. Beneath the surface lies boiling water and unstable ground. Fatal falls into hot springs have occurred.

In mountainous regions, leaving trails increases risk of falls, rockslides, and getting lost. Rescue operations become more complex and time-sensitive.

The human error here is curiosity mixed with complacency. The terrain may appear stable. The shortcut may look faster.

But in nature, appearances deceive.

Underestimating Water

Water environments consistently produce deadly human mistakes.

Rip currents at beaches pull swimmers out to sea. Many victims panic and attempt to swim directly back to shore against the current, exhausting themselves. The correct survival technique — swimming parallel to shore — is often unknown or forgotten in panic.

Boating accidents frequently involve lack of life jackets. Calm water can turn rough quickly due to sudden weather shifts.

Flash floods present another underestimated danger. In canyons and dry riverbeds, rainfall miles away can send walls of water through narrow passages within minutes. Campers caught unaware may have no escape route.

Water does not appear aggressive — until it moves.

Disregarding Wildlife Boundaries

Human-wildlife interactions often become deadly when people ignore warning signs.

Tourists approach bison in Yellowstone for photographs, misjudging their speed and strength. Moose, often seen as passive, can charge during mating season. Elephants, when startled, can become lethal.

Predator encounters sometimes escalate because humans misinterpret behavior — running from a big cat, feeding wild animals, or failing to store food properly in bear country.

The error is anthropomorphism: assuming animals will respond calmly or predictably.

Wild animals operate on instinct, not courtesy.

Inadequate Preparation

Improper gear and lack of planning are recurring themes in wilderness fatalities.

Climbers without avalanche training venture into unstable snowfields. Hikers without navigation tools become lost after sunset. Desert travelers fail to inform others of their route.

In remote regions, small mistakes escalate because rescue is delayed. A twisted ankle can become life-threatening without communication.

Preparation is not paranoia — it is risk management.

Pushing Beyond Turnaround Time

In mountaineering, there is a concept called “turnaround time” — a predetermined hour when climbers must descend regardless of how close they are to the summit.

Several Everest deaths occurred when climbers ignored turnaround times, pushing for the summit late in the day. Fatigue, altitude sickness, and fading daylight combine into lethal conditions.

The summit remains. The opportunity can return. The descent must happen.

Ambition sometimes overrides discipline.

Trusting Technology Too Much

Modern tools — GPS devices, weather apps, satellite phones — improve safety. But overreliance can backfire.

Batteries die. Signals fail. Weather models are not perfect.

Some hikers have followed GPS directions into hazardous terrain when digital maps lacked topographical detail.

Technology enhances safety, but it cannot replace judgment.

Real-Life Tragedies Caused by Human Error in Nature

The 1996 Everest Disaster – When Ambition Overrides Judgment

On May 10–11, 1996, multiple expeditions were attempting to summit Mount Everest. The weather window appeared acceptable. Clients had paid large sums for guided climbs. Pressure — financial and personal — hung over the mountain.

Several critical errors converged:

-

Climbers exceeded the established turnaround time.

-

Fixed ropes were not fully set in advance, causing delays.

-

Bottlenecks formed near the summit.

-

Oxygen supplies ran low.

-

A sudden storm moved in faster than expected.

Eight climbers died within 24 hours.

The mountain did not change its rules. Altitude above 8,000 meters — the “death zone” — impairs judgment, slows reaction time, and drains strength. The error was not ignorance of risk; it was underestimating how quickly conditions could deteriorate once small delays accumulated.

In high-risk environments, minor schedule slips can cascade into catastrophe.

The 2003 Mount Hood Tragedy – Underestimating Conditions

In 2003, three experienced climbers ascended Mount Hood in Oregon. Weather conditions worsened rapidly. One climber fell into a crevasse. The others attempted rescue.

Rescue teams were mobilized, but severe weather and whiteout conditions delayed access. Only one climber survived.

Mount Hood is climbed frequently and is considered accessible compared to Himalayan peaks. Yet familiarity can breed reduced caution. Even experienced climbers can become trapped by sudden storms and unstable snowpack.

Here, nature did not behave unusually. It behaved exactly as mountains often do. The fatal element was underestimating how quickly a routine climb could turn into a survival crisis.

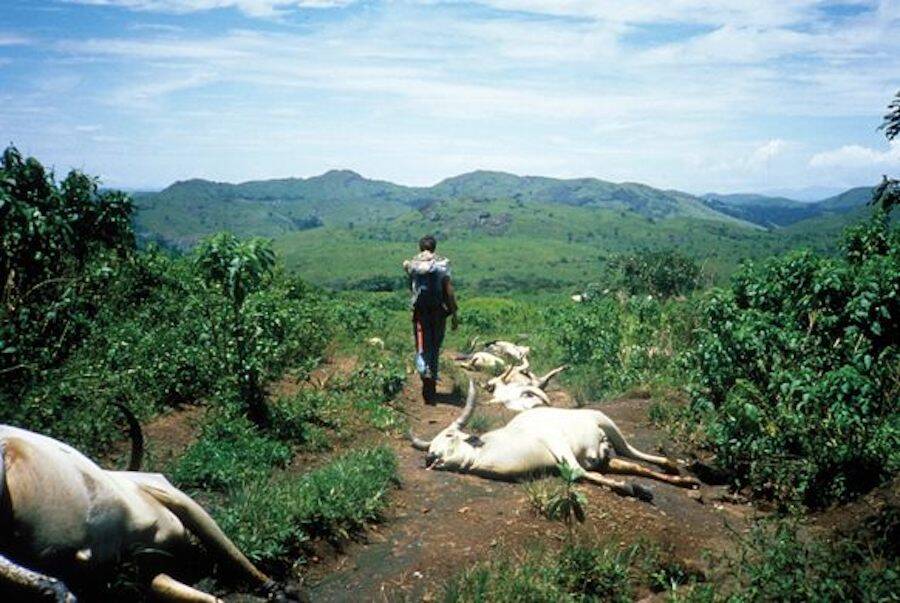

The Lake Nyos Disaster – Invisible Environmental Risk

In 1986, Lake Nyos in Cameroon released a massive cloud of carbon dioxide from its depths. The gas, heavier than air, flowed downhill and suffocated over 1,700 people in nearby villages.

While this event was natural, human settlement near the lake increased vulnerability. The risk of limnic eruption — sudden gas release from deep volcanic lakes — was not widely understood at the time.

After the disaster, degassing systems were installed to reduce future risk.

This case highlights another deadly human error: living near natural hazards without understanding underlying geological processes.

Sometimes, danger is invisible and silent.

Flash Flooding in Slot Canyons

Slot canyons in the American Southwest are stunning, narrow sandstone formations carved by water. They are also death traps during storms.

In 1997, a group of tourists in Antelope Canyon were caught in a flash flood triggered by rainfall miles away. Eleven people died as water surged through the narrow passage.

Flash floods can occur even under clear skies at the canyon site. Rainfall upstream funnels rapidly through confined spaces.

The fatal error is assuming visible weather equals safe conditions. In desert terrain, danger often originates out of sight.

The 2019 Whakaari (White Island) Eruption

In December 2019, tourists were visiting Whakaari, an active volcanic island in New Zealand, when it erupted unexpectedly. Twenty-two people died.

Volcanic monitoring had indicated elevated activity, but the eruption occurred without clear short-term warning.

Tourism operations continued because volcanic systems often fluctuate without erupting. The decision to allow visits balanced economic activity with perceived risk.

The tragedy exposed the difficulty of interpreting incomplete data in dynamic natural systems.

Human error here lay not in ignorance of risk, but in how risk thresholds were defined.

The Role of Cognitive Bias in Wilderness Fatalities

Across these case studies, patterns emerge:

-

Summit fever: Prioritizing goal completion over safety.

-

Familiarity bias: Assuming routine environments remain predictable.

-

Authority bias: Trusting leaders even when conditions change.

-

Optimism bias: Believing disaster will not happen this time.

These biases operate quietly. They distort perception gradually rather than dramatically.

Nature does not need extreme force to become deadly. It only needs a small window of misjudgment.

Lessons That Repeat

The deadliest human errors in nature are rarely dramatic acts of recklessness. More often, they are incremental decisions:

-

“We can push a little further.”

-

“The weather will probably hold.”

-

“It’s only a short distance.”

-

“We’ve done this before.”

In controlled environments, these decisions may carry minimal consequence. In extreme natural settings, they can be fatal.

Nature does not negotiate with confidence, ambition, or habit. It responds only to physics.

And physics does not bend for optimism.